Problem A. 897. (January 2025)

Problem A. 897. (January 2025)

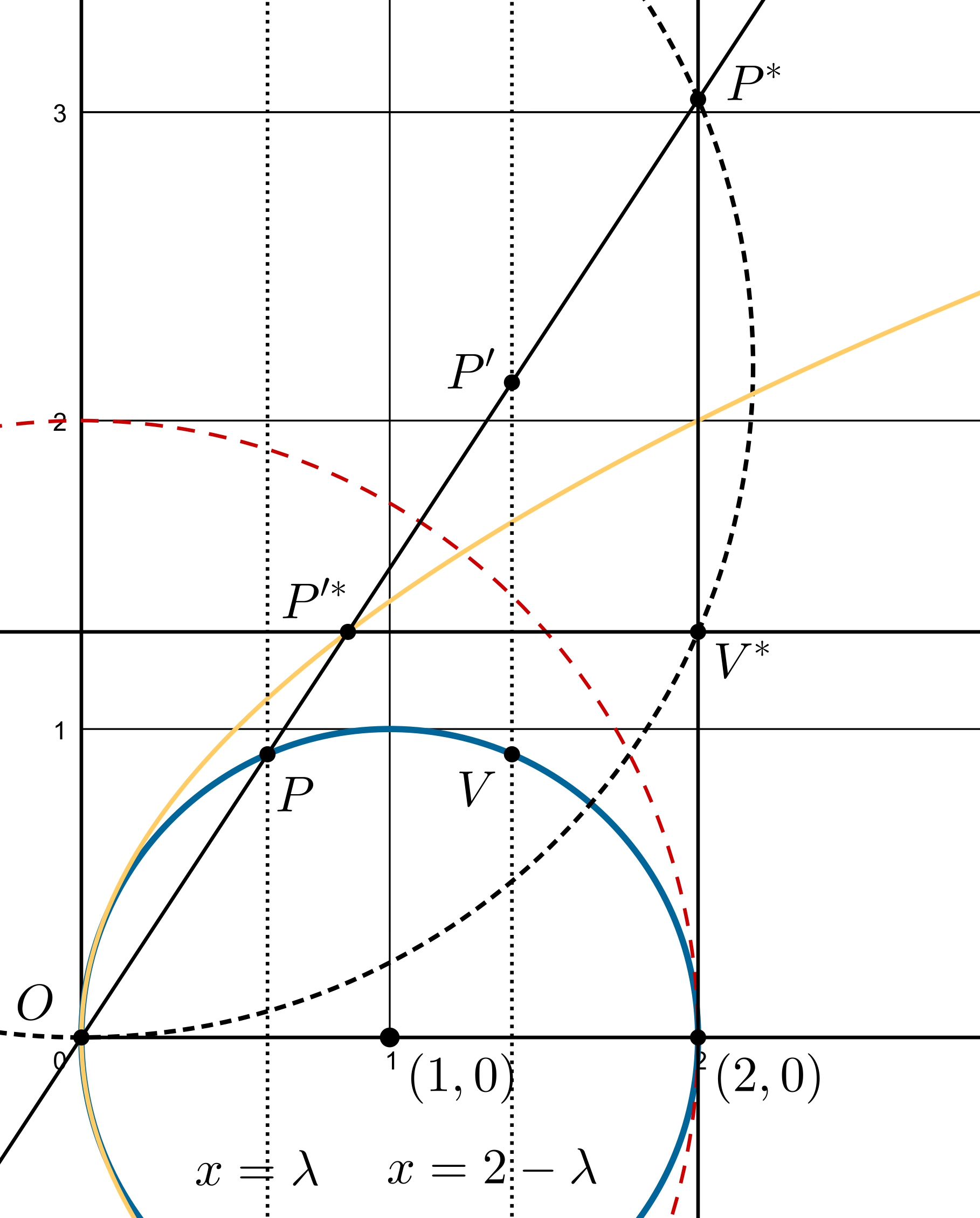

A. 897. Let \(\displaystyle O\) denote the origin and let \(\displaystyle \gamma\) be the circle with center \(\displaystyle (1,0)\) and radius 1 in the Cartesian system of coordinates. Let \(\displaystyle \lambda\) be a real number from the interval \(\displaystyle (0,2)\), and let the line \(\displaystyle x=\lambda\) intersect the circle \(\displaystyle \gamma\) at points \(\displaystyle P\) and \(\displaystyle Q\). The lines \(\displaystyle OP\) and \(\displaystyle OQ\) intersect the line \(\displaystyle x=2-\lambda\) at the points \(\displaystyle P'\) and \(\displaystyle Q'\), respectively. Let \(\displaystyle \mathcal{G}\) denote the locus of such points \(\displaystyle P'\) and \(\displaystyle Q'\) as \(\displaystyle \lambda\) varies over the interval \(\displaystyle (0,2)\). Prove that there exist points \(\displaystyle R\) and \(\displaystyle S\) different from the origin in the plane such that for every \(\displaystyle A\in \mathcal{G}\) there exists a point \(\displaystyle A'\) on line \(\displaystyle OA\) satisfying

\(\displaystyle A'R^2=(A'S-OS)^2=A'A\cdot A'O. \)

Proposed by: Áron Bán-Szabó, Budapest

Attention! A minor discussion error has slipped into the problem statement. The correct form of the statement to be proven is: \(\displaystyle A'R^2 = (A'S \pm OS)^2 = A'A \cdot A'O.\)

(7 pont)

Deadline expired on February 10, 2025.

First, let us prove that inverting \(\displaystyle \mathcal{G}\) around a circle of radius two centered at the origin results in a horizontal parabola. We will show two types of proofs, in each of which we see that the inverse of \(\displaystyle P'\) moves along a fixed parabola, as axial symmetry is sufficient for this purpose.

I. Calculation method: It is clear that since the origin, \(\displaystyle P\), and the point \(\displaystyle (2,0)\) form the vertices of a right triangle, according to the altitude theorem, we have \(\displaystyle P=(\lambda,\lambda(2-\lambda)^{1/2})\). From here, \(\displaystyle P'\) is obtained by magnifying \(\displaystyle P\) from the origin until its \(\displaystyle x\)-coordinate becomes \(\displaystyle 2-\lambda\), hence \(\displaystyle P'=(2-\lambda,\frac{(2-\lambda)^{3/2}}{\lambda^{1/2}})\). By inverting with respect to the circle centered at the origin with radius \(\displaystyle 2\), the image of the point \(\displaystyle (x,y)\) is \(\displaystyle (\frac{4x}{x^2+y^2},\frac{4y}{x^2+y^2})\), therefore the inverse of \(\displaystyle P'\) is \(\displaystyle \left(\dfrac{4(2-\lambda)}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}},\dfrac{\frac{4(2-\lambda)^{3/2}}{\lambda^{1/2}}}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}}\right)\). We show that this point lies on the parabola defined by \(\displaystyle x=\frac{y^2}{2}\).

$$\begin{align*} \dfrac{1}{2}\left (\dfrac{\frac{4(2-\lambda)^{3/2}}{\lambda^{1/2}}}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}}\right)^2 & = \dfrac{8(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda(2-\lambda)^4+2(2-\lambda)^5+\frac{(2-\lambda)^6}{\lambda}} \\ & = \dfrac{4(2-\lambda)}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}}\cdot \left (\dfrac{2(2-\lambda)^2}{\frac{\lambda(2-\lambda)^4+2(2-\lambda)^5+\frac{(2-\lambda)^6}{\lambda}}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}}}\right) \\ & = \dfrac{4(2-\lambda)}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}}\cdot \left (\dfrac{2(2-\lambda)^2}{\frac{\lambda^2(2-\lambda)^2+2\lambda(2-\lambda)^3+(2-\lambda)^4}{\lambda+(2-\lambda)}}\right) \\ & = \dfrac{4(2-\lambda)}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}}\cdot \left (\dfrac{4(2-\lambda)^2}{\lambda^2(2-\lambda)^2+2\lambda(2-\lambda)^3+(2-\lambda)^4}\right) \\ & = \dfrac{4(2-\lambda)}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}}\cdot \left (\dfrac{4}{\lambda^2+2\lambda(2-\lambda)+(2-\lambda)^2}\right) \\ & = \dfrac{4(2-\lambda)}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}}\cdot \left (\dfrac{4}{4}\right) \\ & = \dfrac{4(2-\lambda)}{(2-\lambda)^2+\frac{(2-\lambda)^3}{\lambda}} \end{align*}$$This was to be shown.

II. Projective, degree-based method: (For this method, refer to Vladyslav Zveryk's article in English, "The Method of Moving Points.") Let \(\displaystyle X^*\) denote the inverse image of the figure \(\displaystyle X\) (point, line, or circle). Let \(\displaystyle V\) denote the intersection of the line \(\displaystyle x=2-\lambda\) with the circle, on the same side of the \(\displaystyle x\)-axis as \(\displaystyle P\). Since the inverse of the circle centered at \(\displaystyle (1,0)\) with radius one is the line \(\displaystyle x=2\), the points \(\displaystyle P^*\) and \(\displaystyle V^*\) are on this line. As \(\displaystyle P^*\) moves linearly along this line, note that the circle \(\displaystyle (OP^*V^*)\) is tangent to the \(\displaystyle x\)-axis, since, when inverted back, \(\displaystyle PV\) is parallel to the axis, and the inversion is angle-preserving. Hence, \(\displaystyle V^*\) moves in a linear fashion as well, since if \(\displaystyle B=(2,0)\), then \(\displaystyle BO^2=BP^*\cdot BV^*\), meaning \(\displaystyle V^*\) is the harmonic partner of \(\displaystyle P^*\) with respect to the points \(\displaystyle (2,2)\) and \(\displaystyle (2,-2)\). Since \(\displaystyle P'V\) is perpendicular to the \(\displaystyle x\)-axis, \(\displaystyle P'^*V^*\) is parallel to the \(\displaystyle x\)-axis, thus the lines \(\displaystyle P'^*V^*\) and \(\displaystyle OP^*\) are linear (through a fixed point and a linearly moving point). Therefore, their intersection, \(\displaystyle P'^*\), is quadratic (it is easy to see that it cannot be linear). Clearly, this quadratic curve contains \(\displaystyle O\), and precisely one ideal point passes through it (when \(\displaystyle P=B\), or \(\displaystyle V=O\)), therefore it is a horizontal parabola centered at the origin.

Let the focus of this parabola be \(\displaystyle F\), and its directrix be \(\displaystyle v\). Then, every point \(\displaystyle A^*\) on the parabola is equidistant from \(\displaystyle F\) and \(\displaystyle v\). Let \(\displaystyle T\) denote the foot of the perpendicular dropped from \(\displaystyle A^*\) to \(\displaystyle v\). Then \(\displaystyle |A^*F|=|A^*T|\). Let \(\displaystyle R\) be the inverse of \(\displaystyle F\) with respect to the circle centered at the origin with radius two, while \(\displaystyle S\) is the center of the inverse of \(\displaystyle v\) - which is a circle. If we now invert the circle passing through \(\displaystyle F\) and \(\displaystyle T\) centered at \(\displaystyle A^*\), we get another circle, whose center we choose as \(\displaystyle A'\). Since the circle centered at \(\displaystyle A^*\) passing through \(\displaystyle T\) touches \(\displaystyle v\), their inverses also touch each other. Moreover, with respect to this circle (namely, the circle centered at \(\displaystyle A^*\) passing through \(\displaystyle T\)), \(\displaystyle A^*\) and the point at infinity are each other's inverses, thus after inversion, \(\displaystyle O\) and \(\displaystyle A\) become each other's inverses with respect to the inverse circle. Thus, if the two (inverted) circles are tangent to each other externally

\(\displaystyle AA'\cdot A'O=A'R^2 \quad \text{and} \quad A'R=A'S-OS,\)

while if the two circles are tangent internally

\(\displaystyle AA'\cdot A'O=A'R^2\qquad \text{and} \qquad A'R=A'S+OS.\)

Statistics:

6 students sent a solution. 7 points: Bodor Mátyás, Minh Hoang Tran, Szakács Ábel, Tianyue DAI, Varga Boldizsár. 5 points: 1 student.

Problems in Mathematics of KöMaL, January 2025