Problem A. 901. (February 2025)

Problem A. 901. (February 2025)

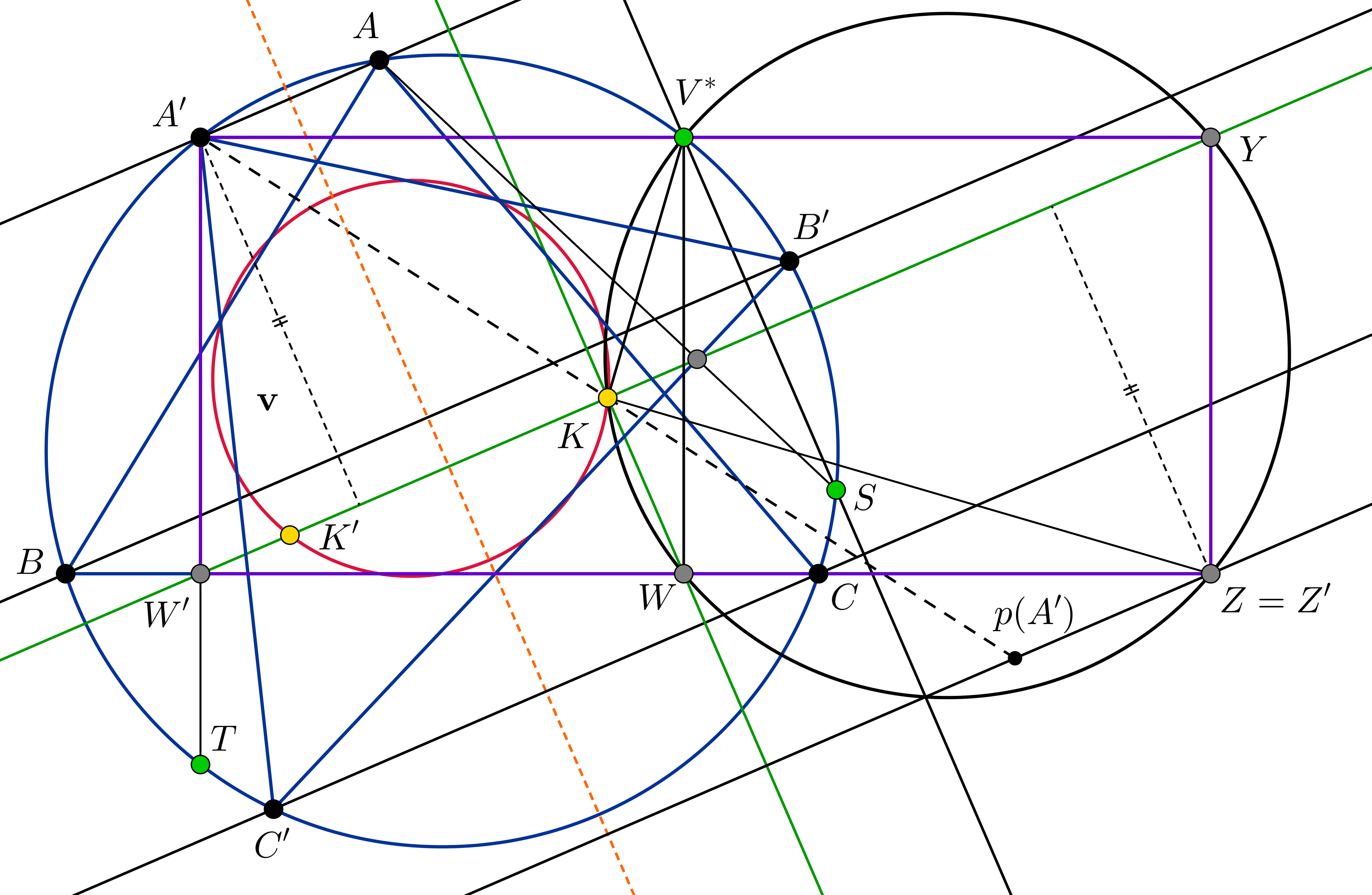

A. 901. Let \(\displaystyle A'B'C'\) denote the reflection of scalene and acute triangle \(\displaystyle ABC\) across its Euler-line. Let \(\displaystyle P\) be an arbitrary point of the nine-point circle of \(\displaystyle ABC\). For every point \(\displaystyle X\), let \(\displaystyle p(X)\) denote the reflection of \(\displaystyle X\) across \(\displaystyle P\). a) Let \(\displaystyle e_{AB}\) denote the line connecting the orthogonal projection of \(\displaystyle A\) to line \(\displaystyle BB'\) and the orthogonal projection of \(\displaystyle B\) to line \(\displaystyle AA'\). Lines \(\displaystyle e_{BC}\) and \(\displaystyle e_{CA}\) are defined analogously. Prove that these three lines are concurrent (and denote their intersection by \(\displaystyle K\)). b) Prove that there are two choices of \(\displaystyle P\) such that lines \(\displaystyle Ap(A')\), \(\displaystyle Bp(B')\) and \(\displaystyle Cp(C')\) are concurrent, and the four points \(\displaystyle p(A)p(A')\cap BC\), \(\displaystyle p(B)p(B')\cap CA\), \(\displaystyle p(C)p(C')\cap AB\), and \(\displaystyle K\) are collinear.

Proposed by: Áron Bán-Szabó, Budapest

(7 pont)

Deadline expired on March 10, 2025.

We will use some well known and some less well known statements. The elementary proofs of these statements can be found in Roger Johnson: Advanced Euclidean Geometry:

- The pedal circles of isogonal conjugates are the same.

Page 155, Theorem 236. - The Simson-line of point \(\displaystyle P\) with respect to triangle \(\displaystyle ABC\) us perpendicular to the \(\displaystyle A\)-isogonal line of line \(\displaystyle AP\).

Page 206, Theorem 326. - The Simson-line of point \(\displaystyle P\) bisects the line segment connecting \(\displaystyle P\) and the orthocenter. This also means that the Steiner-line defined as the line obtained by reflecting \(\displaystyle P\) across the sides of a triangle passes through the orthocenter.

Page 207, Theorem 327. - The Simson-lines of opposite points on the circle are perpendicular and intersect each other on the Nine-point circle.

Page 208, Theorem 328. - \(\displaystyle A\), \(\displaystyle B\), \(\displaystyle C\) and \(\displaystyle D\) are four points in the plane such that no three are collinear. The Nine-point circles of \(\displaystyle ABC\), \(\displaystyle ABD\), \(\displaystyle ACD\) and \(\displaystyle BCD\) has a common point (called the Poncelet point).

Page 242, Theorem 396. - The pedal circle of point \(\displaystyle D\) with respect to triangle \(\displaystyle ABC\) passes through the Poncelet point.

Page 242, Theorem 397.

We introduce some points. Let \(\displaystyle \mathbf{u}\) denote the direction of the Euler line, and let \(\displaystyle \mathbf{v}\) denote the perpendicular to \(\displaystyle \mathbf{u}\). Let point \(\displaystyle V\) be ideal point in direction \(\displaystyle \mathbf{v}\). Let \(\displaystyle H\) denote the orthocenter of \(\displaystyle ABC\). Clearly \(\displaystyle ABC\) and \(\displaystyle A'B'C'\) has the same circumcenter and orthocenter, and also the same Nine-point circle, which we denote by \(\displaystyle \gamma\).

Let's define the Poncelet point of \(\displaystyle A\), \(\displaystyle B\), \(\displaystyle C\) and \(\displaystyle V\): let's consider a sequence of points \(\displaystyle V_i\) tending to \(\displaystyle V\), and note that the Poncelet points corresponding to \(\displaystyle A\), \(\displaystyle B\), \(\displaystyle C\) and \(\displaystyle V_i\) will be bounded, since they are on the fixed circle \(\displaystyle \gamma\), so a convergent subsequence of these points can be found (from now on this subsequence is denoted by \(\displaystyle V_i\)), and their limit will be defined as our point. We claim that \(\displaystyle K\) will be this point. Let's find the limit of the Nine-point circles of \(\displaystyle ABV_i\). Since line \(\displaystyle BV_i\) tends to \(\displaystyle BB'\) by the definition of \(\displaystyle B'\), therefore the foot of the perpendicular of \(\displaystyle A\) to \(\displaystyle BV_i\) will tend to the foot of the perpendicular from \(\displaystyle A\) to \(\displaystyle BB'\), and a similar statement holds for the foot of the perpendicular from \(\displaystyle B\) to \(\displaystyle AA'\), and since the radius of the circle tends to infinity, the limit will be the line \(\displaystyle e_{AB}\), which has to pass through the point we've defined above. The same holds for \(\displaystyle e_{BC}\) and \(\displaystyle e_{AC}\), thus we have proved the first statement.

Note that we have also showed the \(\displaystyle K \in \gamma\). We prove that \(\displaystyle K\) will be a good choice for \(\displaystyle P\). First observe that reflection \(\displaystyle S\) of \(\displaystyle H\) in \(\displaystyle K\) is on the circumcircle, since \(\displaystyle H\) is the internal homothetic center of the circumcircle and \(\displaystyle \gamma\) (with ratio 2). Since \(\displaystyle V\) is ideal, its isogonal conjugate \(\displaystyle V^*\) is on the circumcircle, and he Simson-line of \(\displaystyle V^*\) has direction \(\displaystyle \mathbf{u}\). Since this is the same as the pedal-cirle (which is a line in this case) of \(\displaystyle V\) with respect to \(\displaystyle ABC\), we can deduce that the Simson-line of \(\displaystyle V^*\) passes through \(\displaystyle K\). Thus if we enlarge it from \(\displaystyle H\) with ratio 2, this becomes line \(\displaystyle V^*S\), and therefore this line has direction \(\displaystyle \mathbf{u}\). Now this means that reflectiong \(\displaystyle S\) across the Euler-line we get point \(\displaystyle T\) opposite \(\displaystyle V^*\). The Simson-line of \(\displaystyle T\) wuth respect to \(\displaystyle ABC\) has direction \(\displaystyle \mathbf{v}\), therefore its reflection across the Euler-line is the same line, but at the same time it's the Simson-line of \(\displaystyle S\) with respect to \(\displaystyle A'B'C'\). Now we are ready to prove a key statement: \(\displaystyle SA\) is perpendicular to \(\displaystyle B'C'\).

To this end let \(\displaystyle S'\) be the second intersection of the perpendicular from \(\displaystyle S\) to \(\displaystyle B'C'\) and the circumcircle, and let \(\displaystyle H'\) be the second intersection of \(\displaystyle A'H\) and the circumcircle. Since \(\displaystyle A'H\) and \(\displaystyle SS'\) are both perpendicular to \(\displaystyle B'C'\), this means that \(\displaystyle A'S'\) and the reflection of \(\displaystyle SH'\) across \(\displaystyle B'C'\) are parallel to each other (\(\displaystyle A'S'SH'\) is a symmetric trapezoid and its axis of symmetry is parallel to \(\displaystyle B'C'\)). However, if we reflect \(\displaystyle SH'\) across \(\displaystyle B'C'\), we get the Steiner-line of \(\displaystyle S\) with respect to \(\displaystyle A'B'C'\), therefore we get a line parallel to the Simson-line of \(\displaystyle S\) with respect to \(\displaystyle A'B'C'\), however, we've already established that this line has direction \(\displaystyle \mathbf{v}\), and since \(\displaystyle AS'\) is also perpendicular to \(\displaystyle \mathbf{u}\), we've finally proved that \(\displaystyle A'A\) and \(\displaystyle A'S'\) are parallel to each other, hence \(\displaystyle A=S'\), and this is what we wanted to prove. Finally, since \(\displaystyle Sp(A')\) is the reflection of \(\displaystyle A'H\) across \(\displaystyle K\), and \(\displaystyle AS\) and \(\displaystyle Sp(A')\) are parallel to each other (both being parallel to \(\displaystyle A'H\)), therefore \(\displaystyle A\), \(\displaystyle S\) and \(\displaystyle p(A')\) are collinear, and so \(\displaystyle Ap(A')\) passes through \(\displaystyle S\). The same applies for \(\displaystyle Bp(B')\) and \(\displaystyle Cp(C')\) and so we are done.

Now we show that the perpendicular from \(\displaystyle K\) to \(\displaystyle V^*K\) will pass through point \(\displaystyle Z=p(A)p(A')\cap BC\). In other words, we have to show that \(\displaystyle ZK\perp ZV^*\). Let \(\displaystyle W\) denote the orthogonal projection of \(\displaystyle V^*\) to line \(\displaystyle BC\). Let \(\displaystyle Z'\) denote the intersection of line \(\displaystyle BC\) and circle \(\displaystyle (V^*KW)\). We want to show that \(\displaystyle Z=Z'\), since in this case \(\displaystyle \angle V^*KZ=\angle V^*WZ=90^\circ\). Let \(\displaystyle W'\) be the orthogonal projection of \(\displaystyle A'\) on line \(\displaystyle BC\) and let \(\displaystyle K'\) be the reflection of \(\displaystyle K\) across the Euler-line. We've already shown that the Simson-line of \(\displaystyle S\) with respect to triangle \(\displaystyle A'B'C'\) is \(\displaystyle KK'\) and \(\displaystyle AS\perp B'C'\), therefore the orthogonal projection of point \(\displaystyle A'\) to line \(\displaystyle BC\), namely \(\displaystyle W'\) is on \(\displaystyle KK'\). Since we've already seen that \(\displaystyle A'V^*\) is also perpendicular to line \(\displaystyle AW'=AT\), \(\displaystyle A'W'WV^*\) is a rectangle. Since \(\displaystyle WK\perp KK'\), then point \(\displaystyle Y\) opposite point \(\displaystyle W\) on circle \(\displaystyle (V^*KW)\) is on line \(\displaystyle KK'\). This shows that quadrilateral \(\displaystyle V^*WZ'Y\) is also a rectangle. But then \(\displaystyle A'W'Z'Y\) is a rectangle, too. Therefore \(\displaystyle Z'\) and \(\displaystyle A'\) has the same distance from line \(\displaystyle W'Y\), ie. from line \(\displaystyle KK'\). Thus the line through \(\displaystyle Z'\) in direction \(\displaystyle \mathbf{v}\) is the reflection of line \(\displaystyle AA'\) across point \(\displaystyle K\), and therefore \(\displaystyle Z=Z'\).

Now we are ready to find a second point satisfying the conditions in the problem. We claim that \(\displaystyle K'\) is also good. Since \(\displaystyle KK'\) is perpendicular to the Euler-line, line \(\displaystyle p(A)p(A')\) is the same as in the case of \(\displaystyle P=K\). This clearly shows that the second condition is satisfied, therefore we only need to check that lines \(\displaystyle Ap(A')\), \(\displaystyle Bp(B')\) and \(\displaystyle Cp(C')\) are concurrent. We will prove that all of them pass though the orthocenter \(\displaystyle H\). In other words, we have to show that \(\displaystyle Ap(A')\perp BC\). Reflecting to the Euler-line we get the following: we have to show that connecting \(\displaystyle A\) to the reflection of \(\displaystyle A'\) across \(\displaystyle K\) is perpendicular to \(\displaystyle B'C'\). This is the consequence of an earlier obervation: \(\displaystyle K\) is halfway between the parallel lines \(\displaystyle AS\) and \(\displaystyle A'H\), since \(\displaystyle K\) bisects line segment \(\displaystyle HS\).

Finally \(\displaystyle K\) and \(\displaystyle K'\) has to be different. The only way the could coincide if \(\displaystyle K\) would be on the Euler-line. Since the Simson-line of \(\displaystyle V^*\) is of direction \(\displaystyle \mathbf{u}\), the Simson-line and the Euler-line would be the same, and therefore it would pass through \(\displaystyle H\), which is only possible if \(\displaystyle V^*\) is on the Simpson-line, but that's only possible if it coincides with one of the vertices, and then the Euler-line passes through a vertex, which is only possible for isosceles triangles.

Statistics:

9 students sent a solution. 7 points: Keresztély Zsófia, Varga Boldizsár, Virág Tóbiás. 5 points: 3 students. 4 points: 1 student. 2 points: 2 students.

Problems in Mathematics of KöMaL, February 2025