Problem A. 902. (March 2025)

Problem A. 902. (March 2025)

A. 902. In triangle \(\displaystyle ABC\), interior point \(\displaystyle D\) is chosen such that triangle \(\displaystyle BCD\) is equilateral. Let \(\displaystyle E\) be the isogonal conjugate of point \(\displaystyle D\) with respect to triangle \(\displaystyle ABC\). Define point \(\displaystyle P\) on the ray \(\displaystyle AB\) such that \(\displaystyle AP = BE\). Similarly, define point \(\displaystyle Q\) on the ray \(\displaystyle AC\) such that \(\displaystyle AQ = CE\). Prove that line \(\displaystyle AD\) bisects segment \(\displaystyle PQ\).

Proposed by: Áron Bán-Szabó, Budapest

(7 pont)

Deadline expired on April 10, 2025.

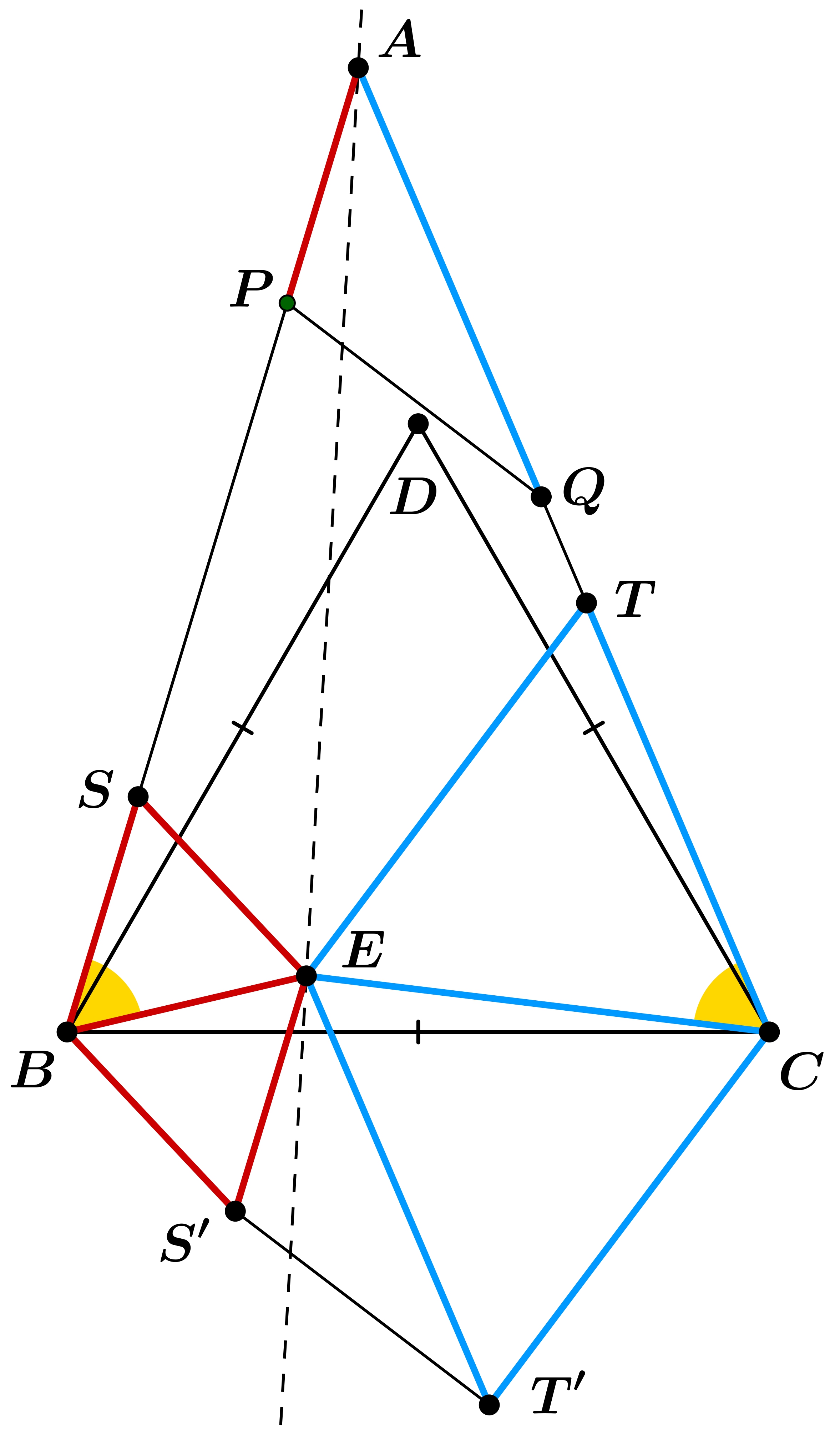

First solution (using symmedians): On the rays \(\displaystyle BA \) and \(\displaystyle CA \), choose points \(\displaystyle S \) and \(\displaystyle T \), respectively, such that \(\displaystyle BS = BE \) and \(\displaystyle CT = CE \). Since \(\displaystyle \angle EBA = \angle EBS = \angle ECA = \angle ECT = 60^\circ \), the triangles \(\displaystyle BES \) and \(\displaystyle CET \) are equilateral.

Now, take points \(\displaystyle S' \) and \(\displaystyle T' \) such that the quadrilaterals \(\displaystyle BSES' \) and \(\displaystyle CTET' \) are parallelograms. Consequently, the triangles \(\displaystyle BES' \) and \(\displaystyle CET' \) are also equilateral. Note that the segments \(\displaystyle ES', SB, AP \) are parallel and have equal length. Similarly, the segments \(\displaystyle ET', TC, AQ \) are also parallel and have equal length, so translating triangle \(\displaystyle APQ \) by the vector \(\displaystyle \overrightarrow{AE} \) gives triangle \(\displaystyle ES'T' \).

The original statement to prove is that line \(\displaystyle AD \) bisects the segment \(\displaystyle PQ \). This is equivalent to the statement that line \(\displaystyle AE \) is a symmedian in triangle \(\displaystyle APQ \), since the lines \(\displaystyle AD \) and \(\displaystyle AE \) are isogonal. The translation does not affect this, so it is enough to prove that line \(\displaystyle AE \) is a symmedian in triangle \(\displaystyle ES'T' \).

It is known that in a triangle, the symmedian from a vertex is the locus of points such that the ratio of the distances to the adjacent sides is equal to the ratio of the lengths of those sides (more precisely, there are two such lines, and we need the one that passes through the triangle). So it suffices to prove that \(\displaystyle d(A,ES')/d(A,ET') = ES'/ET' \), where \(\displaystyle d \) denotes distance.

Now, \(\displaystyle d(A,ES') = d(AB,ES') = d(SB,ES') \), since lines \(\displaystyle AB \) and \(\displaystyle ES' \) are parallel; and due to the equilateral triangles, this distance is \(\displaystyle \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \cdot ES' \). Similarly, \(\displaystyle d(A,ET') = d(AC,ET') = d(TC,ET') = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \cdot ET' \), so indeed \(\displaystyle d(A,ES')/d(A,ET') = ES'/ET' \). We are done.

Second solution (using moving points): We will use a known lemma:

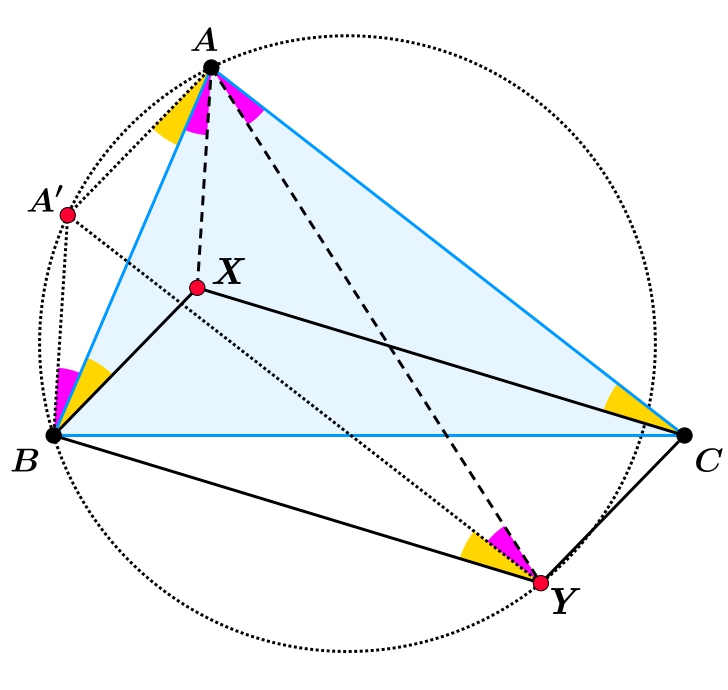

Lemma: Given a triangle \(\displaystyle ABC \) (not the one from the problem), and a point \(\displaystyle X \) inside it such that \(\displaystyle \angle XBA = \angle ACX \). Let \(\displaystyle Y \) be the point such that \(\displaystyle BXCY \) is a parallelogram. Then the points \(\displaystyle X \) and \(\displaystyle Y \) are isogonal conjugates with respect to point \(\displaystyle A \).

Proof: Let \(\displaystyle A' \) be the point such that the quadrilaterals \(\displaystyle AXBA' \) and \(\displaystyle ACYA' \) are parallelograms. Then \(\displaystyle \angle A'AB = \angle XBA = \angle ACX = \angle A'YB \), since \(\displaystyle AC \parallel A'Y \) and \(\displaystyle XC \parallel BY \). Therefore, the points \(\displaystyle A, A', B, Y \) lie on a circle. Using this, we get that \(\displaystyle \angle BAX = \angle ABA' = \angle AYA' = \angle YAC \). This proves the lemma.

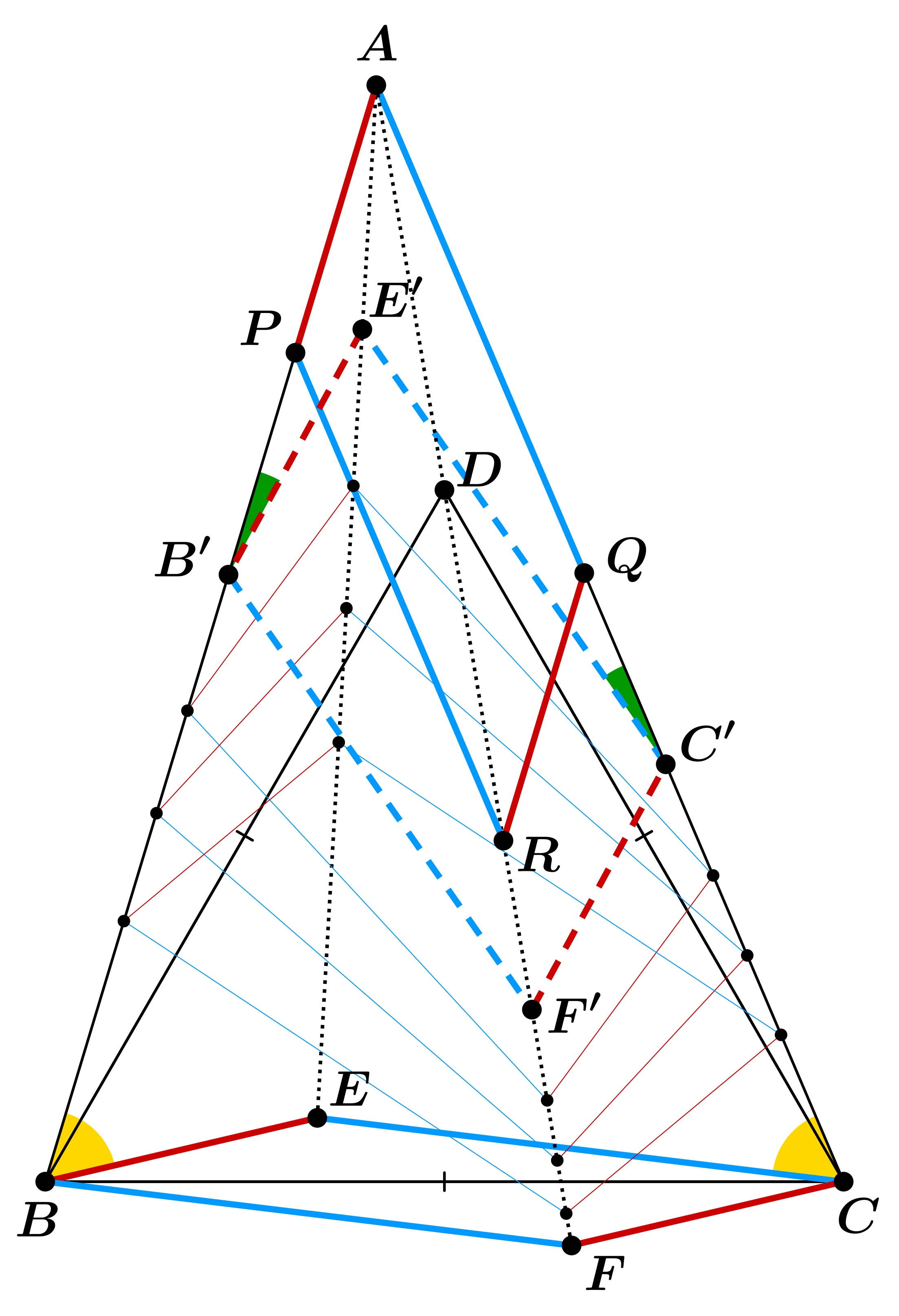

Now we return to the problem. Let \(\displaystyle F \) be the reflection of point \(\displaystyle E \) across the midpoint of side \(\displaystyle BC \), and let \(\displaystyle R \) be the reflection of point \(\displaystyle A \) across the midpoint of segment \(\displaystyle PQ \). Since \(\displaystyle \angle EBA = \angle DBC = 60^\circ = \angle BCD = \angle ACE \), we can use our lemma to conclude that the lines \(\displaystyle AE \) and \(\displaystyle AF \) are isogonal with respect to point \(\displaystyle A \). But since \(\displaystyle AD \) and \(\displaystyle AE \) are also isogonal, it is enough to show that points \(\displaystyle A, R, F \) lie on a straight line.

Imagine building a physical model of the problem. Think of the sides of the parallelogram \(\displaystyle BECF \) as rods of fixed length. Consider the rays \(\displaystyle AB \) and \(\displaystyle AC \) as rails along which the points \(\displaystyle B \) and \(\displaystyle C \) can slide. This way if we move point \(\displaystyle E \) slightly, we still have a parallelogram with sides of length \(\displaystyle BE \) and \(\displaystyle CE \), and with one pair of opposite vertices constrained to lie on the \(\displaystyle AB \) and \(\displaystyle AC \) rails. It is enough to prove that as we move point \(\displaystyle E \) linearly towards point \(\displaystyle A \), point \(\displaystyle F \) also moves linearly towards point \(\displaystyle A \); because when \(\displaystyle E \) reaches \(\displaystyle A \), then \(\displaystyle B \) moves to \(\displaystyle P \), \(\displaystyle C \) moves to \(\displaystyle Q \), and \(\displaystyle F \) moves to \(\displaystyle R \).

Suppose we stop at some moment as we move \(\displaystyle E \) towards \(\displaystyle A \). Let the current position of the parallelogram \(\displaystyle BECF \) be \(\displaystyle B'E'C'F' \). We know that the triples \(\displaystyle A-B-B' \), \(\displaystyle A-C-C' \), and \(\displaystyle A-E-E' \) are collinear. We want to show that the triple \(\displaystyle A-F-F' \) is also collinear, which is equivalent to showing that the lines \(\displaystyle AE' \) and \(\displaystyle AF' \) are isogonal with respect to \(\displaystyle A \). To do this, we want to use the lemma in triangle \(\displaystyle AB'C' \) with point \(\displaystyle E' \). For that, we need \(\displaystyle \angle E'B'A = \angle AC'E' \).

We use the known statement that if two triangles have a pair of sides with equal length and the angles opposite to those sides are equal, then their circumcircles are congruent (by the inscribed angle theorem). Conversely, if two triangles have congruent circumcircles and a pair of sides with equal length, then the angles opposite to those sides are either equal or sum to \(\displaystyle 180^\circ \).

In triangles \(\displaystyle ABE \) and \(\displaystyle AB'E' \), we have \(\displaystyle BE = B'E' \) and the angle at \(\displaystyle A \) is common, so their circumcircles are congruent. In triangles \(\displaystyle ABE \) and \(\displaystyle ACE \), the side \(\displaystyle AE \) is common, and the angles opposite to it are both \(\displaystyle 60^\circ \), so their circumcircles are congruent. Finally, in triangles \(\displaystyle ACE \) and \(\displaystyle AC'E' \), we have \(\displaystyle CE = C'E' \) and again the angle at \(\displaystyle A \) is common, so their circumcircles are congruent.

Thus, we conclude that the circumcircles of triangles \(\displaystyle AB'E' \) and \(\displaystyle AC'E' \) are congruent. The side \(\displaystyle AE' \) is common, and it is easy to see that \(\displaystyle \angle AB'E' + \angle E'C'A \neq 180^\circ \), so indeed \(\displaystyle \angle E'B'A = \angle AC'E' \). This proves the claim.

The above reasoning does not apply in the special case when \(\displaystyle E = A \). However, since \(\displaystyle F \) moves along the line \(\displaystyle AF \) as we draw \(\displaystyle E \) linearly towards \(\displaystyle A \), by continuity, as \(\displaystyle E \) approaches \(\displaystyle A \), point \(\displaystyle F \) approaches a point on the line \(\displaystyle AF \). We are done.

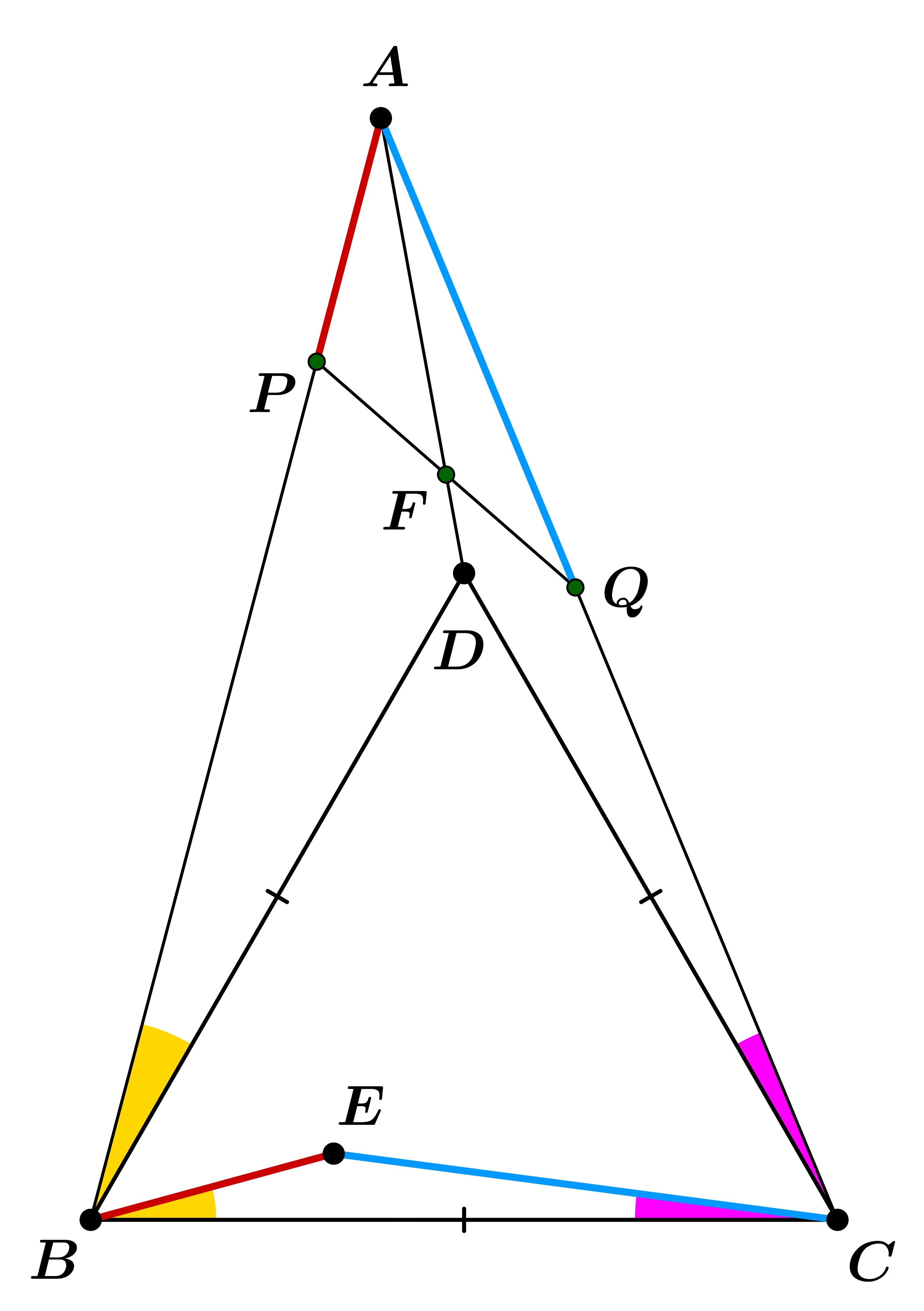

Third solution (using the Law of Sines): Let \(\displaystyle F \) be the intersection point of lines \(\displaystyle PQ \) and \(\displaystyle AD \). We want to prove that \(\displaystyle PF = FQ \). Apply the Law of Sines in triangles \(\displaystyle APF \) and \(\displaystyle AFQ \):

\(\displaystyle PF = AF \cdot \frac{\sin \angle PAF}{\sin \angle FPA}, \quad FQ = AF \cdot \frac{\sin \angle FAQ}{\sin \angle AQF}. \)

So it is enough to prove that

\(\displaystyle \frac{\sin \angle PAF}{\sin \angle FPA} = \frac{\sin \angle FAQ}{\sin \angle AQF}, \)

which is equivalent to

\(\displaystyle \frac{\sin \angle AQF}{\sin \angle FPA} = \frac{\sin \angle FAQ}{\sin \angle PAF}. \)

Using the Law of Sines in triangle \(\displaystyle APQ \), and the fact that \(\displaystyle AP = BE \) and \(\displaystyle AQ = CE \), we get:

\(\displaystyle \frac{BE}{CE} = \frac{AP}{AQ} = \frac{\sin \angle AQP}{\sin \angle QPA} = \frac{\sin \angle AQF}{\sin \angle FPA}. \)

Thus, we reduce the original claim to proving:

\(\displaystyle \frac{BE}{CE} = \frac{\sin \angle FAQ}{\sin \angle PAF}. \)

Now apply the Law of Sines in triangle \(\displaystyle BEC \), and use the definition of isogonal conjugates, which tells us that \(\displaystyle \angle CBE = \angle DBA \) and \(\displaystyle \angle ECB = \angle ACD \). Then:

\(\displaystyle \frac{BE}{CE} = \frac{\sin \angle ECB}{\sin \angle CBE} = \frac{\sin \angle ACD}{\sin \angle DBA}. \)

Therefore, the original statement reduces to showing:

\(\displaystyle \frac{\sin \angle FAQ}{\sin \angle PAF} = \frac{\sin \angle ACD}{\sin \angle DBA}, \)

which is equivalent (by expressing the angles appropriately) to:

\(\displaystyle \frac{\sin \angle DAC}{\sin \angle ACD} = \frac{\sin \angle BAD}{\sin \angle DBA}. \)

Finally, using the fact that triangle \(\displaystyle BCD \) is equilateral, we know \(\displaystyle BD = CD \), and applying the Law of Sines in triangles \(\displaystyle ACD \) and \(\displaystyle ADB \), we obtain:

\(\displaystyle \frac{\sin \angle DAC}{\sin \angle ACD} = \frac{CD}{AD} = \frac{BD}{AD} = \frac{\sin \angle BAD}{\sin \angle DBA}. \)

This completes the proof.

Statistics:

14 students sent a solution. 7 points: Aravin Peter, Bodor Mátyás, Bui Thuy-Trang Nikolett, Czanik Pál, Forrai Boldizsár, Holló Martin, Keresztély Zsófia, Sha Jingyuan, Szakács Ábel, Varga Boldizsár, Virág Tóbiás. 6 points: Tianyue DAI, Xiaoyi Mo. 0 point: 1 student.

Problems in Mathematics of KöMaL, March 2025