Problem A. 906. (April 2025)

Problem A. 906. (April 2025)

A. 906. Let \(\displaystyle \mathcal{V}_c\) denote the infinite parallel ruler with the parallel edges being at distance \(\displaystyle c\) from each other. The following construction steps are allowed using ruler \(\displaystyle \mathcal{V}_c\):

\(\displaystyle \bullet\) the line through two given points;

\(\displaystyle \bullet\) line \(\displaystyle l'\) parallel to a given line \(\displaystyle l\) at distance \(\displaystyle c\) (there are two such lines, both of which can be constructed using this step);

\(\displaystyle \bullet\) for given points \(\displaystyle A\) and \(\displaystyle B\) with \(\displaystyle |AB|\ge c\) two parallel lines at distance \(\displaystyle c\) such that one of them passes through \(\displaystyle A\), and the other one passes through \(\displaystyle B\) (if \(\displaystyle |AB|>c\), there exists two such pairs of parallel lines, and both can be constructed using this step). On the perimeter of a circular piece of paper three points are given that form a scalene triangle. Let \(\displaystyle n\) be a given positive integer. Prove that based on the three points and \(\displaystyle n\) there exists \(\displaystyle C>0\) such that for any \(\displaystyle 0<c\le C\) it is possible to construct \(\displaystyle n\) points using only \(\displaystyle \mathcal{V}_c\) on one of the excircles of the triangle. We are not allowed to draw anything outside our circular paper. We can construct on the boundary of the paper; it is allowed to take the intersection point of a line with the boundary of the paper.

Proposed by: Áron Bán-Szabó, Budapest

(7 pont)

Deadline expired on May 12, 2025.

We will first prove a few important lemmas, supposing that we have straightedge \(\displaystyle \nu_c\) for some small \(\displaystyle c\). Let \(\displaystyle \Omega\) be the circumcircle of the three given points. We will check the feasibility of the main construction steps, and we will check the existence of constant \(\displaystyle C\) at the end of our proof.

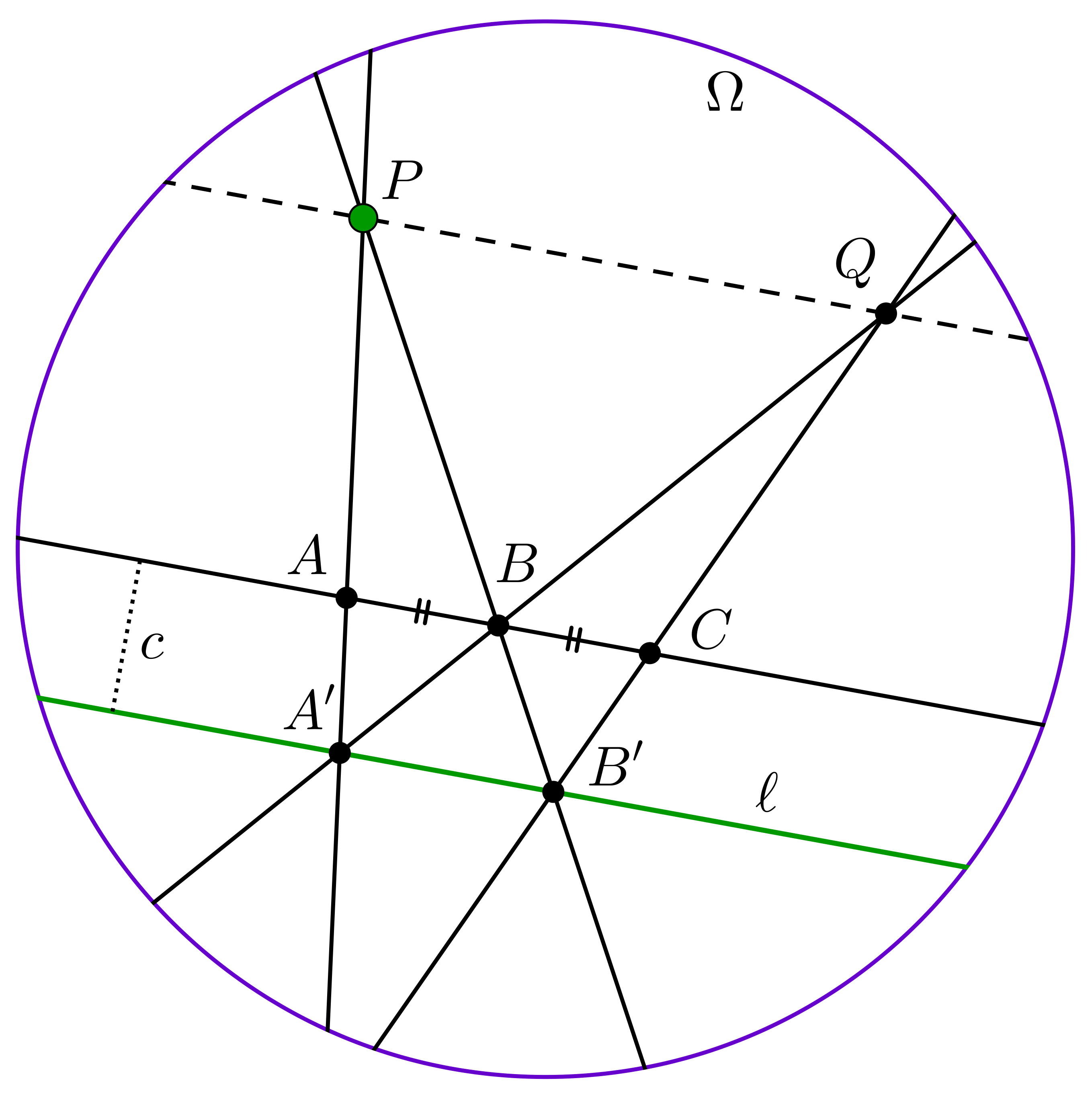

Lemma 1. Let points \(\displaystyle B\) be given inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\) and line \(\displaystyle \ell\) intersecting \(\displaystyle \Omega\) in two points. We can construct a line parallel to \(\displaystyle \ell\) through \(\displaystyle P\).

Proof. We draw a line parallel to \(\displaystyle \ell\) using \(\displaystyle \nu_c\). Let's choose points \(\displaystyle A\), \(\displaystyle B\) and \(\displaystyle C\) on this parallel line such that \(\displaystyle B\) is the midpoint of \(\displaystyle AC\). In order to achieve this, we draw three parallel lines at distance \(\displaystyle c\) from each other intersecting \(\displaystyle \ell\) in three points satisfying our requirement. Let lines \(\displaystyle PA\) and \(\displaystyle PB\) intersect \(\displaystyle \ell\) in \(\displaystyle A'\) and \(\displaystyle B'\), and let \(\displaystyle A'B\) and \(\displaystyle B'C\) intersect each other in \(\displaystyle Q\). We claim that \(\displaystyle PQ||\ell\). Indeed, \(\displaystyle PB/BB'=AB/(A'B'-AB)=BC/(A'B'-BC)=QB/BA'\), therefore triangles \(\displaystyle BB'A'\) and \(\displaystyle BPQ\) are similar, and thus \(\displaystyle A'B'\) and \(\displaystyle PQ\) are parallel.

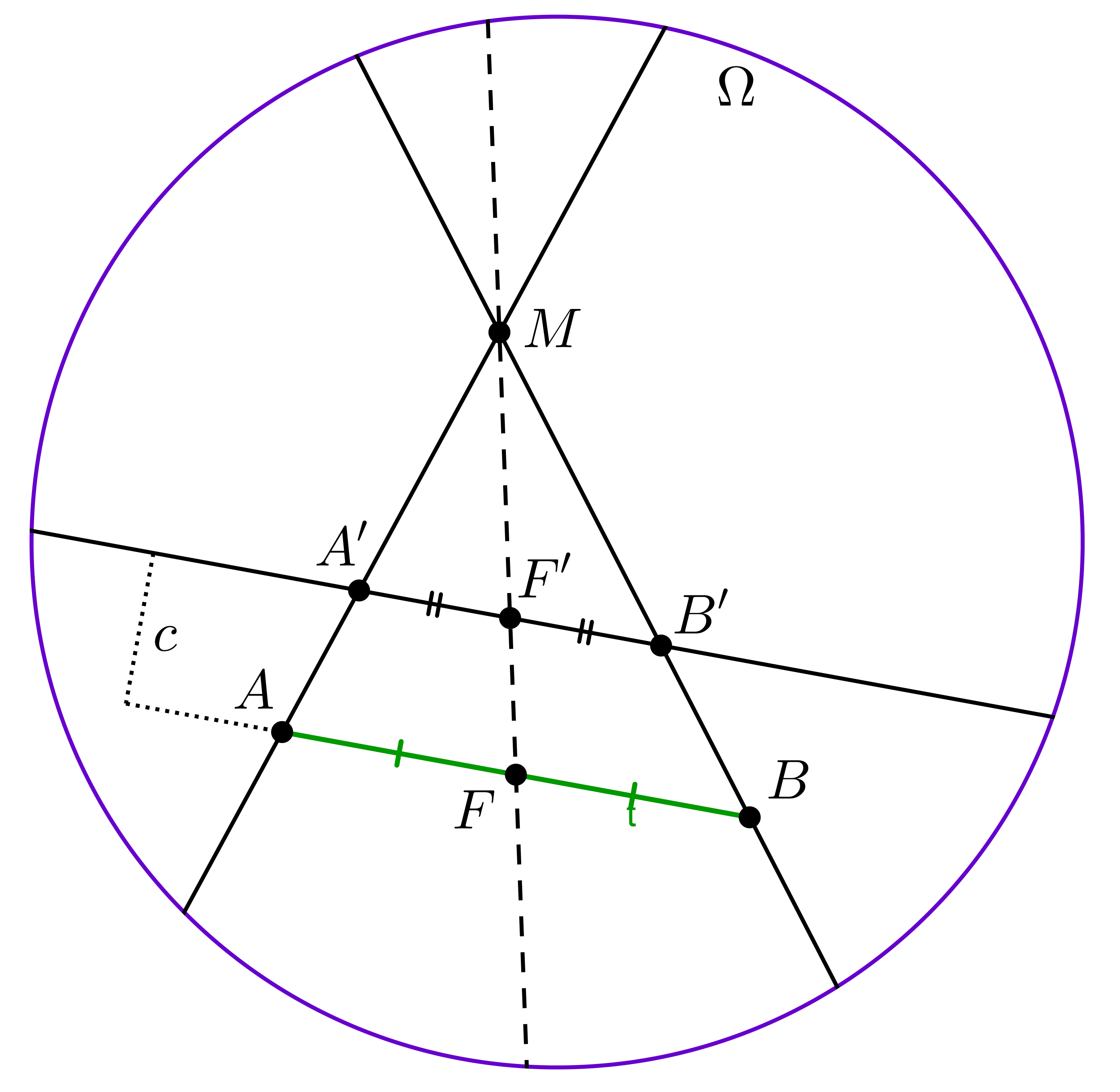

Lemma 2. If line segment \(\displaystyle AB\) is inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\) or on \(\displaystyle \Omega\), we can construct the midpoint of \(\displaystyle AB\).

Proof. Let's draw a line parallel to \(\displaystyle AB\), and let's draw points \(\displaystyle A'\), \(\displaystyle B'\) and \(\displaystyle F'\) such that \(\displaystyle F'\) is the midpoint of \(\displaystyle A'B'\) (this can be done the same way as in the previous part). Let \(\displaystyle M\) be the intersection of \(\displaystyle AA'\) and \(\displaystyle BB'\). Then \(\displaystyle MF'\) will intersect \(\displaystyle AB\) in its midpoint \(\displaystyle F\).

Lemma 3. We can do point reflection inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\) as long as the reflection is also inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\).

Proof. Same as the previous part, just \(\displaystyle A\) and \(\displaystyle F\) is given and \(\displaystyle B\) has to be obtained.

Lemma 4. We ca construct the center of \(\displaystyle \Omega\) and we for any given point and line inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\) we can construct the perpendicular to the given line through the given point.

Proof. First draw two parallel chords in \(\displaystyle \Omega\), then construct their midpoints. The line connecting the midpoints will pass through the center. Repeat the same steps with a second pair of parallel chords, and thus obtain the center. If a line is given, construct the midpoint of the chord defined by the line, connect it to the center, and draw a parallel to this line through the given point.

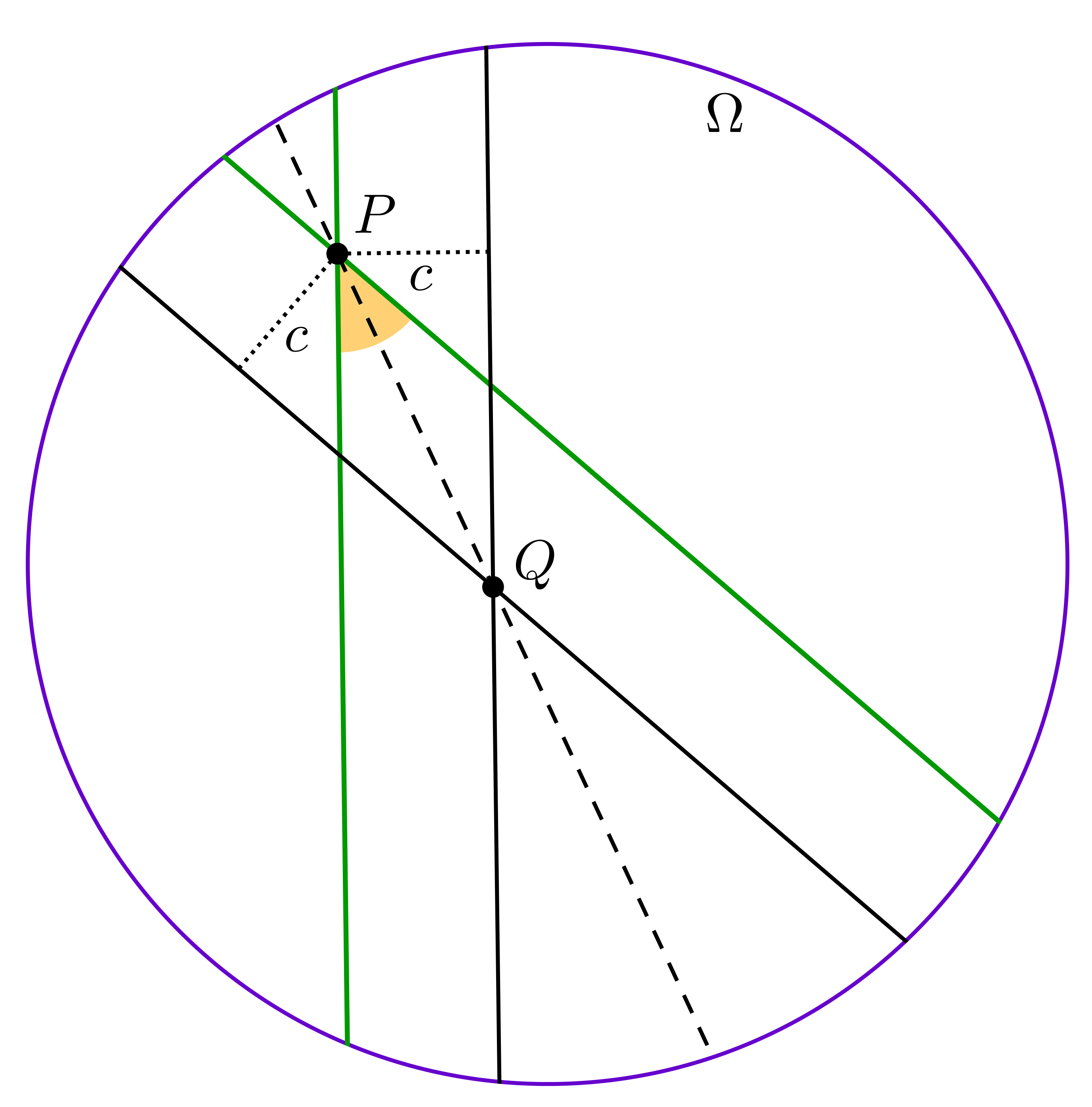

Lemma 5. If two lines intersect each other inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\), we can construct the angle bisectors of them.

Proof. Draw two lines at distance \(\displaystyle c\) from the two given lines, and connect their intersection to the intersection of the given lines (depending on which side of the given lines are they chosen, we can obtain both angle bisectors).

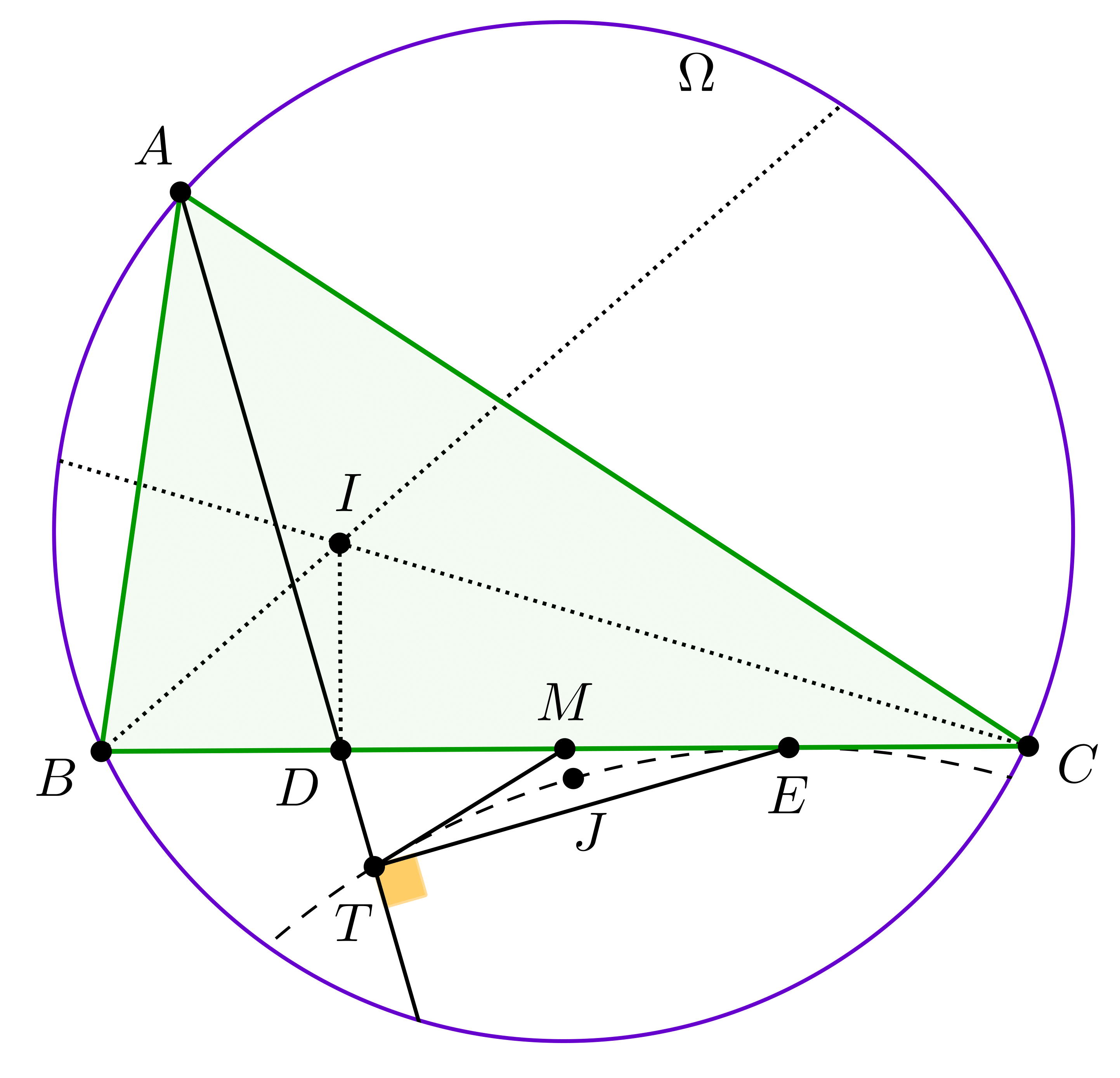

Finally we will construct \(\displaystyle n\) points on an excircle of the given three points. Suppose that our triangle is \(\displaystyle ABC\), and that angles \(\displaystyle \angle B\) and \(\displaystyle \angle C\) are acute angles (there is at most one non-acute angle in a triangle). Let's contruct incenter \(\displaystyle I\) of the given triangle (as an intersection of two interior angle bisectors). The perpendicular from \(\displaystyle I\) to \(\displaystyle BC\) will intersect \(\displaystyle BC\) in \(\displaystyle D\), which is the point of tangency of the incircle on side \(\displaystyle BC\). We can construct midpoint \(\displaystyle M\) of \(\displaystyle BC\), and the reflection \(\displaystyle E\) of \(\displaystyle D\) across \(\displaystyle M\), which will be the point of tangency of the excircle corresponding to side \(\displaystyle BC\).

Finally, let's construct \(\displaystyle T\), the foot of the perpendicular from \(\displaystyle E\) to \(\displaystyle AD\). Since \(\displaystyle \angle B\) and \(\displaystyle \angle C\) are acute angles, \(\displaystyle T\) will be inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\). We claim that \(\displaystyle T\) lies on the excircle corresponding to side \(\displaystyle BC\). To prove this, consider the homothety mapping the incircle to the excircle. It's well known that \(\displaystyle E\) will be the image of \(\displaystyle D'\), which is the antipode of \(\displaystyle D\) on the incircle. Therefore, the foot of the perpendicular from \(\displaystyle D'\) to \(\displaystyle AD\) will be mapped to \(\displaystyle T\). However, this since \(\displaystyle DD'\) is a diameter in the incircle, so this point must also be on the incircle, and thus \(\displaystyle T\) will be on the excircle.

Now we claim that the incenter \(\displaystyle J\) of triangle \(\displaystyle MTE\) is also on the excircle. Indeed, since \(\displaystyle MT=ME\) (\(\displaystyle M\) is the midpoint of hypotenuse \(\displaystyle DE\) of right triangle \(\displaystyle DTE\)), and \(\displaystyle ME\) is tangent to the excircle, \(\displaystyle MT\) also must be tangent to the excircle. Now if \(\displaystyle J'\) is the midpoint of arc \(\displaystyle TE\), it's easy to see that \(\displaystyle \angle MTJ'=\angle J'ET=\angle J'TE\), and therefore \(\displaystyle TJ'\) is the angle bisector of \(\displaystyle \angle ETM\). By symmetry, \(\displaystyle J'\) must be the incenter of \(\displaystyle MTE\).

Finally, if we have an obtuse triangle \(\displaystyle PQR\), where \(\displaystyle \angle Q\) is the obtuse angle, we can contruct any number of points arc \(\displaystyle PQR\) of its circumcircle: if the three points are \(\displaystyle P\), \(\displaystyle Q\) and \(\displaystyle R\), then the interior angle bisector of \(\displaystyle \angle R\) and the perpendicular bisector of \(\displaystyle PQ\) will intersect each other in the midpoint of the smaller arc \(\displaystyle PQ\).

We have to check that by choosing \(\displaystyle c\) sufficiently small, all the above contructions can be carried out on our piece of paper.

In Lemma 1 \(\displaystyle A\), \(\displaystyle B\) and \(\displaystyle C\) will be inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\) if \(\displaystyle c\) is sufficiently small, and \(\displaystyle Q\) will also be inside, since \(\displaystyle PQ=AB\times d(\ell,PQ)/d(\ell,AB)\). If \(\displaystyle Q\) is not inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\), we can construct a second parallel to \(\displaystyle AB\) at distance \(\displaystyle c\) and repeat the same construction, thereby increasing \(\displaystyle d(\ell,AB)\) and thus decreasing \(\displaystyle PQ\). If \(\displaystyle c\) is small enough, this can be repeated several times to make \(\displaystyle PQ\) sufficiently small, thus guaranteeing that \(\displaystyle Q\) is inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\).

In Lemma 2 we have to make sure that \(\displaystyle M\) is inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\). If we move points \(\displaystyle A'\), \(\displaystyle B'\) and \(\displaystyle F'\) on line \(\displaystyle A'B'\) such that distance \(\displaystyle A'F'=F'B'\) remains fixed, then \(\displaystyle M\) moves on a line parallel to \(\displaystyle AB\). If the next position of \(\displaystyle A'\), \(\displaystyle B'\) and \(\displaystyle F'\) is chosen such that \(\displaystyle A'\) becomes \(\displaystyle F'\) and \(\displaystyle F'\) becomes \(\displaystyle B'\), and the new position of \(\displaystyle B'\) is the reflection of \(\displaystyle F'\) across \(\displaystyle B'\), \(\displaystyle M\) will move with a fixed distance (and obviously this can be done in the other direction as well). If \(\displaystyle c\) is chosen small enough, this distance can also be made arbitrarily small, therefore guaranteeing that after finitely many such steps \(\displaystyle M\) will be inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\).

In Lemmas 3 and 4 we do a finite number of the above steps, therefore we don't need to do anything new here.

In Lemma 5 we only have to make sure that \(\displaystyle Q\) is inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\), and for small enough \(\displaystyle c\) distance \(\displaystyle PQ\) can also be made arbitrarily small, thus guaranteeing that \(\displaystyle Q\) has to be inside \(\displaystyle \Omega\) as well.

Statistics:

7 students sent a solution. 7 points: Aravin Peter, Bodor Mátyás, Forrai Boldizsár, Varga Boldizsár, Xiaoyi Mo. 5 points: 1 student. 0 point: 1 student.

Problems in Mathematics of KöMaL, April 2025