Problem A. 910. (May 2025)

Problem A. 910. (May 2025)

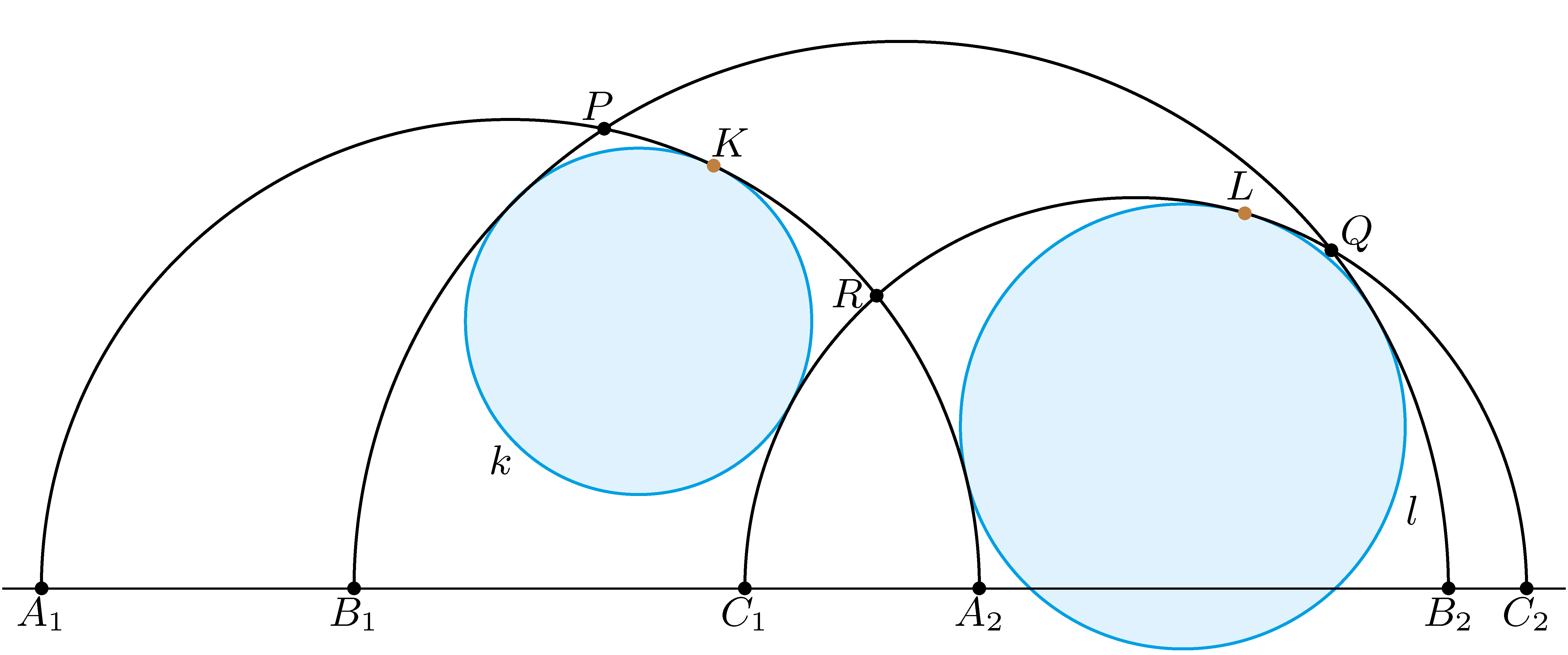

A. 910. Points \(\displaystyle A_1\), \(\displaystyle B_1\), \(\displaystyle C_1\), \(\displaystyle A_2\), \(\displaystyle B_2\), \(\displaystyle C_2\) are collinear in this order. The semicircles with diameters \(\displaystyle A_1A_2\) and \(\displaystyle B_1B_2\) intersect at point \(\displaystyle P\), the semicircles with diameters \(\displaystyle B_1B_2\) and \(\displaystyle C_1C_2\) intersect at point \(\displaystyle Q\), and the semicircles with diameters \(\displaystyle C_1C_2\) and \(\displaystyle A_1A_2\) intersect at point \(\displaystyle R\). Circles \(\displaystyle k\) and \(\displaystyle l\) are tangent to all three semicircles as shown in the figure. Let \(\displaystyle K\) denote the point of tangency of the circle \(\displaystyle k\) and the semicircle with diameter \(\displaystyle A_1A_2\), while let \(\displaystyle L\) denote the point of tangency of the circle \(\displaystyle l\) and the semicircle with diameter \(\displaystyle C_1C_2\).

Prove that \(\displaystyle \frac{A_1R\cdot B_1P\cdot B_2Q\cdot C_2R}{A_2R\cdot B_1Q\cdot B_2P\cdot C_1R}=\frac{A_1K\cdot C_2L}{A_2K\cdot C_1L}\).

(Proposed by: Áron Bán-Szabó, Budapest

(7 pont)

Deadline expired on June 10, 2025.

Let us denote the line \(\displaystyle A_1B_1C_1A_2B_2C_2\) by \(\displaystyle e\). Observe that the statement to be proved can be rewritten as

\(\displaystyle \dfrac{A_1R\cdot A_2K}{A_1K\cdot A_2R}\cdot \dfrac{C_1L\cdot C_2R}{C_1R\cdot C_2L}=\dfrac{B_1Q\cdot B_2P}{B_1P\cdot B_2Q}, \)

which is nothing but

\(\displaystyle (A_1,A_2;R,K)\cdot (C_1,C_2;R,L)=(B_1,B_2;Q,P), \)

where \(\displaystyle (A,B;C,D)=\dfrac{AC\cdot BD}{AD\cdot BC}\) denotes the cross-ratio of the quadruple \(\displaystyle ABCD\).

This may inspire the introduction of a function \(\displaystyle \mathcal{D}\) on the points above the line \(\displaystyle e\), which assigns to any pair of points \(\displaystyle X,Y\) (lying above \(\displaystyle e\)) the cross-ratio

\(\displaystyle \mathcal{D}(X,Y):=(E_2,E_1;X,Y), \)

where \(\displaystyle E_1,E_2\) are the points on the line \(\displaystyle e\) such that \(\displaystyle E_1,X,Y,E_2\) lie in this order on a semicircle with diameter \(\displaystyle E_1E_2\). Such a semicircle exists uniquely, since the intersection of the perpendicular bisector of \(\displaystyle XY\) with \(\displaystyle e\) determines the center. (This is not yet completely sufficient, since such a semicircle only exists if \(\displaystyle XY\not\perp e\), but in the case \(\displaystyle e\perp XY\) we may define \(\displaystyle \mathcal{D}(X,Y)\) as the ratio \(\displaystyle EX/EY\), where \(\displaystyle E=XY\cap e\), and the points \(\displaystyle E,Y,X\) lie in this order on the line \(\displaystyle XY\). It is now easy to verify that our function is indeed well-defined for all point pairs lying above \(\displaystyle e\).)

Ideally, we would like this to be a distance function. However, \(\displaystyle \mathcal{D}(X,Y)\) is always at least \(\displaystyle 1\), and it is not additive on semicircles lying on \(\displaystyle e\) (which serve as lines in our context). We fix this now: define

\(\displaystyle \|XY\|:=\ln(\mathcal{D}(X,Y)). \)

Note that this is now a proper distance function, since it is non-negative, symmetric, additive on semicircles lying on \(\displaystyle e\), and it can be verified that it satisfies the triangle inequality as well. It is important to emphasize that with the distance \(\displaystyle \|.\|\), the lines in the upper half-plane over \(\displaystyle e\) are precisely the semicircles lying on \(\displaystyle e\). That is, by definition, the shortest path between two points lies on the semicircle (or line perpendicular to \(\displaystyle e\)) lying on \(\displaystyle e\) that passes through the two points. We will only need two key lemmas:

Lemma 1. \(\displaystyle \|.\|\) is additive on semicircles lying on \(\displaystyle e\), that is, if the points \(\displaystyle E_1,X,Y,Z,E_2\) lie in this order on a circle with diameter \(\displaystyle E_1E_2\) (where \(\displaystyle E_1,E_2\in e\)), then \(\displaystyle \|XY\|+\|YZ\|=\|XZ\|\).

Proof. We simply observe that

\(\displaystyle \ln \left (\dfrac{E_1Y\cdot E_2X}{E_1X\cdot E_2Y}\right)+\ln \left (\dfrac{E_1Z\cdot E_2Y}{E_1Y\cdot E_2Z}\right)=\ln \left (\dfrac{E_1Y\cdot E_2X\cdot E_1Z\cdot E_2Y}{E_1X\cdot E_2Y\cdot E_1Y\cdot E_2Z}\right)=\ln \left (\dfrac{E_1Z\cdot E_2X}{E_1X\cdot E_2Z}\right).\qquad \square \)

Lemma 2. Let \(\displaystyle \Omega\) be a circle whose center lies above the line \(\displaystyle e\). Suppose that the points \(\displaystyle X\) and \(\displaystyle Y_1,Y_2\in \Omega\) lie above \(\displaystyle e\), and the lines \(\displaystyle XY_1,XY_2\) (that is, semicircles lying on \(\displaystyle e\)) are tangent to \(\displaystyle \Omega\). Then \(\displaystyle \|XY_1\|=\|XY_2\|\).

Proof. Consider the circle \(\displaystyle \omega\) that passes through \(\displaystyle X\), is symmetric with respect to \(\displaystyle e\), and is orthogonal to the circle \(\displaystyle \Omega\). Such a circle exists: think of the circle symmetric to \(\displaystyle e\) passing through \(\displaystyle X\) and the inversion of \(\displaystyle X\) with respect to \(\displaystyle \Omega\). If we invert with respect to this circle \(\displaystyle \omega\), then \(\displaystyle X\) and \(\displaystyle \Omega\) remain fixed, hence \(\displaystyle Y_1\) maps to \(\displaystyle Y_2\) and vice versa, since images of tangent circles remain tangent (and semicircles on \(\displaystyle e\) remain semicircles on \(\displaystyle e\)). Since inversion preserves cross-ratios, it follows that \(\displaystyle \|XY_1\|=\|XY_2\|\). \(\displaystyle \quad \square\)

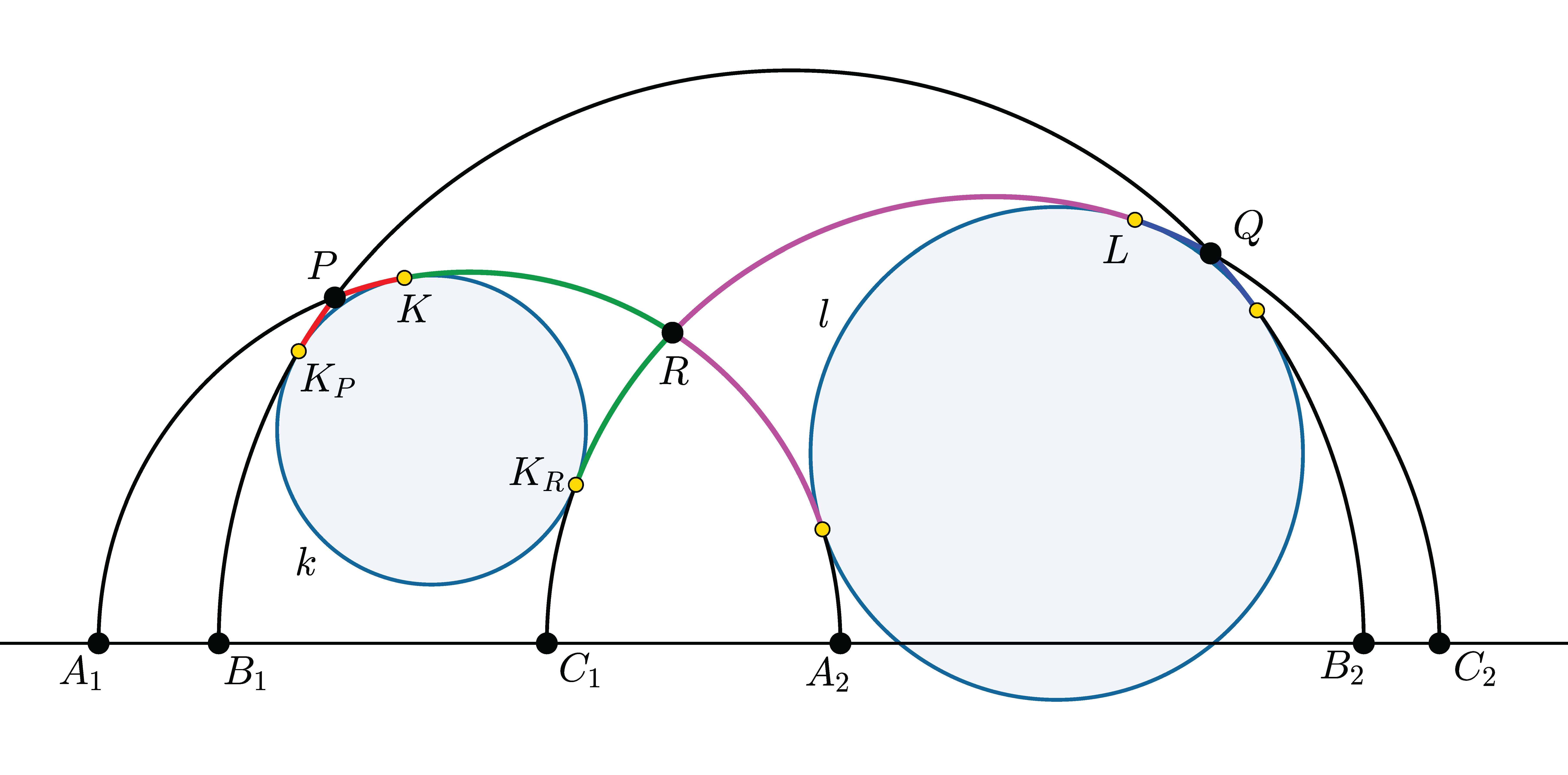

Now let us return to the statement to be proven. We need to show that \(\displaystyle \|KR\|+\|LR\|=\|PQ\|\). Observe that \(\displaystyle k\) and \(\displaystyle l\) are exactly the excircles of triangle \(\displaystyle PQR\). And now the same argument works as in Euclidean geometry: if \(\displaystyle k\) is tangent to the line \(\displaystyle PQ\) at \(\displaystyle K_P\) and tangent to the line \(\displaystyle RQ\) at \(\displaystyle K_R\), then by Lemma 2 we get \(\displaystyle \|QP\|+\|PK_P\|=\|QR\|+\|RK_R\|\), \(\displaystyle \|PK_P\|=\|PK\|\), \(\displaystyle \|RK_R\|=\|RK\|\), and \(\displaystyle \|PK\|=\|RK\|\). From this, a simple calculation yields

\(\displaystyle \|KR\|=\dfrac{\|PR\|+\|PQ\|-\|QR\|}{2}. \)

Similarly, we obtain

\(\displaystyle \|LR\|=\dfrac{\|PQ\|+\|QR\|-\|PR\|}{2}. \)

Hence,

\(\displaystyle \|KR\|+\|LR\|=\dfrac{\|PR\|+\|PQ\|-\|QR\|}{2}+\dfrac{\|PQ\|+\|QR\|-\|PR\|}{2}=\|PQ\|. \)

This is what we intended to prove.

Remark: In fact, we solved the problem using hyperbolic geometry, more precisely in the upper half-plane model, by the equation \(\displaystyle (s-b)+(s-c)=a\) (where \(\displaystyle s\) denotes the half perimeter, and \(\displaystyle a,b,c\) denotes the sides).

Statistics:

2 students sent a solution. 7 points: Varga Boldizsár. 6 points: Forrai Boldizsár.

Problems in Mathematics of KöMaL, May 2025