Problem A. 915. (October 2025)

Problem A. 915. (October 2025)

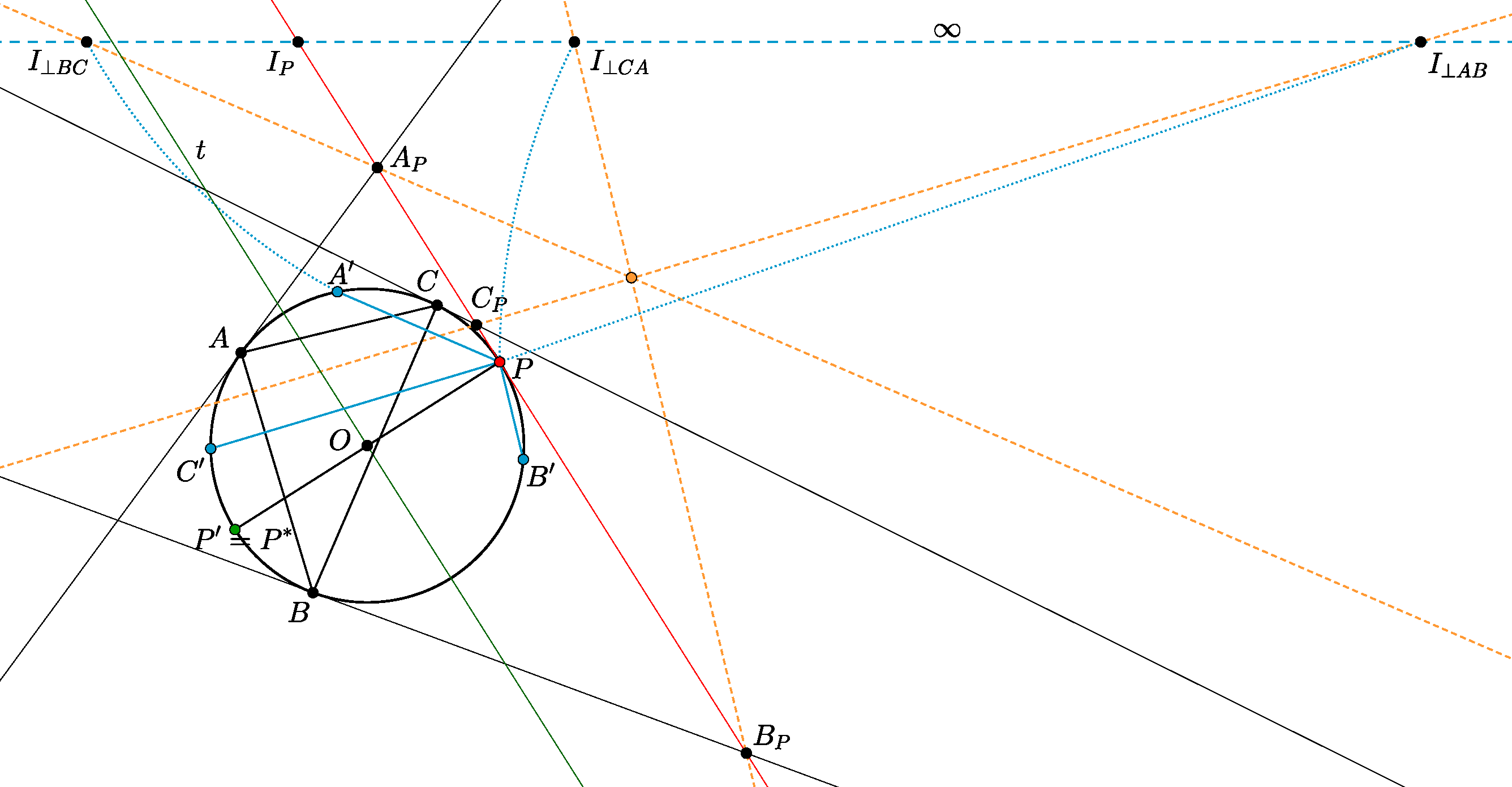

A. 915. Given a circle with three points \(\displaystyle A\), \(\displaystyle B\), and \(\displaystyle C\) on it, which do not form an isosceles triangle. For every point \(\displaystyle P\notin\{A,B,C\}\) on the circle, let \(\displaystyle A_P\), \(\displaystyle B_P\) and \(\displaystyle C_P\) denote the intersections of the tangent at \(\displaystyle P\) with the tangents at \(\displaystyle A\), \(\displaystyle B\), and \(\displaystyle C\), respectively. Prove that there exist exactly three points \(\displaystyle P\notin\{A,B,C\}\) on the circle for which the points \(\displaystyle A_P\), \(\displaystyle B_P\) and \(\displaystyle C_P\) are well-defined and the perpendiculars from \(\displaystyle A_P\) to \(\displaystyle BC\), from \(\displaystyle B_P\) to \(\displaystyle CA\), and from \(\displaystyle C_P\) to \(\displaystyle AB\) are concurrent. Furthermore, show that these three points \(\displaystyle P\) form an equilateral triangle.

Proposed by Zoltán Gyenes, Budapest

(7 pont)

Deadline expired on November 10, 2025.

1. solution: Let \(\displaystyle O\) denote the center of the circle. We will work in the projective plane. Denote the line at infinity schematically by \(\displaystyle \infty\). Let the ideal point of the tangent at \(\displaystyle P\) be \(\displaystyle I_P\), and let \(\displaystyle I_{\perp AB}, I_{\perp BC}, I_{\perp CA}\) denote the ideal points corresponding to the directions perpendicular to the lines \(\displaystyle AB, BC, CA\), respectively. We are interested in those points \(\displaystyle P\) for which the lines \(\displaystyle A_PI_{\perp BC}\), \(\displaystyle B_PI_{\perp CA}\), and \(\displaystyle C_PI_{\perp AB}\) are concurrent. This is equivalent to

\(\displaystyle (A_P,B_P;C_P,I_P)=(I_{\perp BC},I_{\perp CA};I_{\perp AB},I_P). \)

Project from \(\displaystyle P\) the quadruple of points \(\displaystyle (I_{\perp BC},I_{\perp CA};I_{\perp AB},I_P)\): if \(\displaystyle A',B',C'\) denote the second intersection points with the circle of the perpendiculars from \(\displaystyle P\) to the lines \(\displaystyle BC,CA,AB\), respectively, then we obtain that

\(\displaystyle (I_{\perp BC},I_{\perp CA};I_{\perp AB},I_P)=(A',B';C',P) \)

(since the line \(\displaystyle PI_P\) is tangent to the circle).

Note that the triangles \(\displaystyle ABC\) and \(\displaystyle A'B'C'\) are congruent. Moreover, they are images of each other under an axial reflection, whose axis is the line \(\displaystyle t\) through \(\displaystyle O\) perpendicular to the Simson line of \(\displaystyle P\). (This can be verified by a simple angle computation, using the fact that the line \(\displaystyle AP\) is the isogonal of \(\displaystyle A\), that is, its reflection about the bisector of the angle \(\displaystyle BAC\) is perpendicular to the Simson line of \(\displaystyle P\).)

Now let \(\displaystyle P'\) be the reflection of \(\displaystyle P\) with respect to \(\displaystyle t\), and let \(\displaystyle P^*\) be the reflection of \(\displaystyle P\) with respect to \(\displaystyle O\), i.e. the point diametrically opposite to \(\displaystyle P\) on the circle. Returning to the problem, due to the reflection across \(\displaystyle t\), we have \(\displaystyle (A',B';C',P)=(A,B;C,P')\). Furthermore, the pole–polar transformation preserves cross-ratios, so

\(\displaystyle (A_P,B_P;C_P,I_P)=(PA,PB;PC,PO). \)

Projected onto the circle, this gives

\(\displaystyle (PA,PB;PC,PO)=(A,B;C,P^*). \)

Combining these, the statement that the perpendiculars from \(\displaystyle A_P\) to \(\displaystyle BC\), from \(\displaystyle B_P\) to \(\displaystyle CA\), and from \(\displaystyle C_P\) to \(\displaystyle AB\) are concurrent is equivalent to

\(\displaystyle (A,B;C,P')=(A,B;C,P^*), \)

or, equivalently, \(\displaystyle P'=P^*\).

We will show that this holds for exactly three points \(\displaystyle P\), which form the vertices of an equilateral triangle. Choose \(\displaystyle P\) arbitrarily on the circle. Move \(\displaystyle P\) along the circle by a central angle \(\displaystyle x\). It is known that in this case, the Simson line—and thus the axis \(\displaystyle t\)—rotates by \(\displaystyle -\frac{x}{2}\). Due to reflection, \(\displaystyle P'\) rotates by \(\displaystyle -2x\). Since \(\displaystyle P^*\) is simply the image of \(\displaystyle P\) under a \(\displaystyle 180^{\circ}\) rotation around \(\displaystyle O\), it rotates by \(\displaystyle x\). Thus, if we move \(\displaystyle P\) along the circle at a constant rate, \(\displaystyle P^*\) moves at the same rate, but \(\displaystyle P'\) moves twice as fast in the opposite direction. Therefore, the two points will eventually coincide. When does this coincidence occur again? Exactly when \(\displaystyle x+2x=3x\) is a multiple of \(\displaystyle 360^{\circ}\), i.e. \(\displaystyle x=\pm 120^{\circ}\). Hence, the statement is proven.

2. solution: In this solution, we will use complex numbers. We will take the circle in the problem to be the unit circle \(\displaystyle |z|=1\). First, we show that if \(\displaystyle z\neq w\) and \(\displaystyle |z|=|w|=1\), then the tangents to the unit circle at these points intersect at

\(\displaystyle t=\frac{2zw}{z+w}, \)

that is, the harmonic mean of the two given complex numbers. To prove this, we only need to show that \(\displaystyle z\) and \(\displaystyle t-z\) are perpendicular, i.e. that \(\displaystyle \frac{z}{t-z}\) is purely imaginary (by symmetry, \(\displaystyle w\) and \(\displaystyle t-w\) are then also perpendicular).

Let us first simplify the fraction:

\(\displaystyle \frac{z}{t-z}=\frac{z}{\frac{zw-z^2}{z+w}}=\frac{z+w}{w-z}, \)

and this is indeed purely imaginary, since \(\displaystyle z+w\) and \(\displaystyle w-z\) are perpendicular because \(\displaystyle |z|=|w|\).

Now, if \(\displaystyle a\), \(\displaystyle b\), and \(\displaystyle c\) are three given points on the unit circle, then the points in the problem are

\(\displaystyle a_p=\frac{2ap}{a+p},\quad b_p=\frac{2bp}{b+p},\quad c_p=\frac{2cp}{c+p}. \)

Next, let us write the equation of the line perpendicular to \(\displaystyle BC\) and passing through \(\displaystyle A_P\). A point \(\displaystyle Z\) lies on this perpendicular if \(\displaystyle \frac{z-a_p}{b-c}\) is purely imaginary, i.e. if its conjugate is equal to its negative:

\(\displaystyle \frac{z-a_p}{b-c}=-\frac{\overline{z}-\overline{a_p}}{\overline{b}-\overline{c}}. \)

We can now simplify the fraction on the right-hand side using the fact that \(\displaystyle |x|=1\) implies \(\displaystyle \overline{x}=\frac{1}{x}\): first,

\(\displaystyle \overline{a_p}=\frac{2\overline{a}\overline{p}}{\overline{a}+\overline{p}}=\frac{\frac{2}{ap}}{\frac{1}{a}+\frac{1}{p}}=\frac{2}{a+p}, \)

and hence

\(\displaystyle \frac{\overline{z}-\overline{a_p}}{\overline{b}-\overline{c}}=\frac{\overline{z}-\frac{2}{a+p}}{\frac{1}{b}-\frac{1}{c}}=\frac{bc\overline{z}-\frac{2bc}{a+p}}{c-b}, \)

so the equation of the required line becomes

\(\displaystyle z-\frac{2ap}{a+p}=bc\overline{z}-\frac{2bc}{a+p}. \)

Now we can compute the intersection of the perpendicular from \(\displaystyle A_P\) to \(\displaystyle BC\) and the perpendicular from \(\displaystyle B_P\) to \(\displaystyle AC\): subtracting the two equations gives

\(\displaystyle \frac{2bp}{b+p}-\frac{2ap}{a+p}=(bc-ac)\overline{z}-\frac{2bc}{a+p}+\frac{2ac}{b+p}, \)

that is,

\(\displaystyle \frac{2(b-a)p^2}{(a+p)(b+p)}=c(b-a)\overline{z}+\frac{2(a^2-b^2)c+2(a-b)cp}{(a+p)(b+p)}, \)

whence

\(\displaystyle \overline{z}=2\cdot\frac{p^2+(a+b+p)c}{c(a+p)(b+p)}. \)

Thus, the condition that the three perpendiculars pass through a common point becomes

\(\displaystyle \frac{p^2+(a+b+p)c}{c(a+p)(b+p)}=\frac{p^2+(b+c+p)a}{a(b+p)(c+p)}, \)

from which

\(\displaystyle a(c+p)\left(p^2+(a+b+p)c\right)=c(a+p)\left(p^2+(b+c+p)a\right), \)

and after expanding,

\(\displaystyle ap^3+2acp^2+(a+b+c)acp+ac^2(a+b)=cp^3+2acp^2+(a+b+c)acp+a^2c(b+c), \)

which simplifies to the equation \(\displaystyle p^3=abc\) (for \(\displaystyle p\neq -a,-b,-c\), the transformations were equivalent, since we did not divide or multiply by zero). The three solutions indeed form an equilateral triangle. It remains to check when a solution coincides with one of \(\displaystyle a,b,c,-a,-b,-c\): for instance, if \(\displaystyle a^3=abc\), then \(\displaystyle bc=a^2\), and the triangle is isosceles, since this is equivalent to \(\displaystyle OA\) being perpendicular to \(\displaystyle BC\), where \(\displaystyle O\) is the circumcenter of \(\displaystyle \triangle ABC\). Unfortunately, equality with \(\displaystyle -a\) is possible: in that case \(\displaystyle a^2=-bc\), i.e. \(\displaystyle OA\) is parallel to \(\displaystyle BC\) (equivalently, the difference between the angles at \(\displaystyle B\) and \(\displaystyle C\) is \(\displaystyle 90^\circ\)), which was not mentioned in the original conditions of the problem.

Statistics:

26 students sent a solution. 7 points: Ali Richárd, Aravin Peter, Bodor Mátyás, Bolla Donát Andor, Bui Thuy-Trang Nikolett, Diaconescu Tashi, Ethan Y.Wang, Forrai Boldizsár, Gyenes Károly, Li Mingdao, Szakács Ábel, Tianyue DAI, Vigh 279 Zalán, Vincze Marcell, Vödrös Dániel László. 6 points: Prohászka Bulcsú, Sárdinecz Dóra. 5 points: 1 student. 4 points: 1 student. 0 point: 5 students. Unfair, not evaluated: 2 solutionss.

Problems in Mathematics of KöMaL, October 2025